NEW YORK — New details are emerging about how a failed COVID-19 containment response by city officials sowed chaos among agency staff and left vulnerable detained youth at greater risk of contracting the disease.

Though the New York Police Department has yet to release an official statement, staff inside the Crossroads facility and their union confirmed details of Monday’s incident, when nearly 50 officers were called to squelch a fracas at Crossroads Juvenile Center on Monday, and the policies that sparked it.

The policy, which involved shifting incarcerated youth in the city into the Crossroads facility in Brooklyn, was roundly criticized by experts who said the responsible city agency had failed to respond to heightened anxiety from staff and youth surrounding the coronavirus pandemic.

The policy, which involved shifting incarcerated youth in the city into the Crossroads facility in Brooklyn, was roundly criticized by experts who said the responsible city agency had failed to respond to heightened anxiety from staff and youth surrounding the coronavirus pandemic.

“They lost all control” on Monday, said Darek Robinson, vice president of Union 371, which represents staff at Crossroads facility. “No managers were on duty, there weren't enough special officers to secure the building; that’s why they made the call to NYPD.”

For days afterward the Administration for Children’s Services (ACS), which runs the detention facility, refused to even confirm the incident. However, on Wednesday, ACS spokesperson Sam Chafee released the following statement by email:

“Our top priority is protecting the safety and wellbeing of youth and staff in our secure detention facility,” the statement said. “We took immediate action to de-escalate the situation and secure the safety of our youth and staff.”

Short on staff, protective gear

The reality of this ongoing situation appears much more complex.

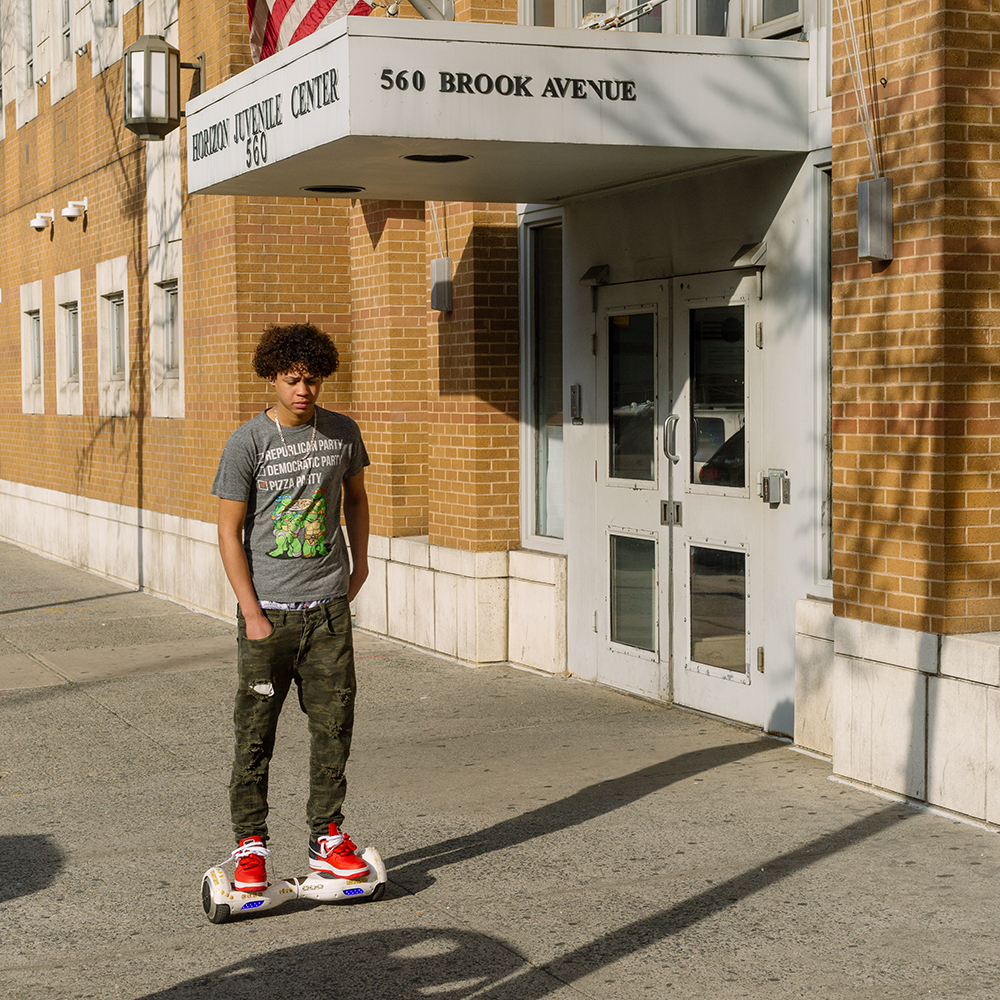

Last month, as ACS began preparing for the pandemic along with the rest of the city, its leaders went against the advice of its staff by designating Crossroads to house healthy residents, and Horizon Juvenile Center in the Bronx, the other city-run detention facility, to house sick residents.

This had the effect of significantly disrupting the lives of the young residents and destabilizing a very delicate rapport between them and the staff at each facility, staff and former guards said.

According to Robinson, nearly 35 employees at Crossroads have tested positive for the virus — including Patricia George, a beloved veteran of the agency who died earlier this month from COVID-19. Critics say the agency has been slow to implement even the most basic viral testing for staff, often having employees self-report symptoms of a disease that may only manifest itself, if at all, well after the patient has begun infecting others.

“They made an inadequate statement for the past two weeks saying they had nurses at both facilities to check the staff entering to work,” Robinson said. “Check their temperature, check their vital signs, which they didn’t. [Wednesday] was the first time there was a nurse in the lobby [of Crossroads].”

Even the most basic equipment to keep staff and residents safe has also been nearly impossible to find within ACS facilities, he said. Critical gear like face masks have often been in short supply, with employees only being issued a single reusable mask that they are expected to wash and reuse between shifts.

Chafee said ACS has begun distributing masks to all frontline staff who come into contact with children and families in the field, but did not specify what kinds of masks were being provided.

Robinson, who frequently interacts with staff inside Crossroads, said the masks given to both guards and medical staff are inadequate, providing little support to the wearer.

“They gave the staff a cloth mask — with strings on it — it looks like something somebody's next-door grandma would make,” Robinson said. “It’s got wide open pockets, with air coming through the side. There’s no way in hell that mask is keeping out any infectious diseases in the air.”

People who work in and have access to the facility said there is a chasm between official policies from ACS leaders and how those policies are being implemented on the frontlines. Robinson said there aren’t enough cleaning staff to clean the facility as well as it needs to be to prevent the spread of COVID-19. And the staff there doesn’t have the training to sanitize the facility properly, he said.

“I’m not asking them to cure the virus, I’m not faulting them for the virus. I’m faulting them for not taking the proper precautions during the virus,” he said.

One source familiar with circumstances inside Crossroads said the cleaning staff have not received any formal training on how to properly clean or to put cleaning outfits on and off. Recently, the source said, a member of the medical staff — who also do not have access to N95 masks — had to explain to a cleaner the proper way to remove his coveralls to avoid cross-contamination.

“The cleaning staff have not been given any training on disinfecting areas,” the source said. “One diligent worker at one of the facilities, he was grateful he had medical staff who gave him instruction on how to more safely remove his overalls. ... It’s scary, he feels he's getting most of his virus training not from the job but from watching TV and looking on the internet.”

Chafee said all youth have their temperature checked every day for fever, one of the possible signs of the coronavirus for people who are not asymptomatic

“As soon as any symptoms are identified, youth are immediately transported to where they are closely monitored by health professionals,” he said. “Similarly, if a youth is symptomatic upon being placed in secure detention, the youth is immediately transported straight to Horizon.”

The mother of a child at Crossroads, who did not want to be identified for fear of imperiling her son's ongoing criminal case, disagreed with the assertion that every young person was having their temperature checked.

“Only the kids who are showing symptoms are being tested regularly,” she said. “My son is not being tested every day, but he isn’t showing any symptoms, luckily.”

Result of fracas

Robinson said the violence that broke out was the result of the misguided consolidation policy and that he had warned that moving youth would lead to trouble, especially since there are what he described as desperately low staffing levels.

Chafee challenged that characterization.

“Safety in our facilities is a top priority, and we have worked hard to create a system of care within our secure juvenile detention system that is grounded in best practice and designed to promote a safe, secure environment for youth and staff,” he said.

The five youth who attacked staff at Crossroads were returned to Horizon, where they were before the consolidation plan. Now sick and healthy youth at Horizon are being kept in separate halls. According to sources familiar with the case, who asked to remain anonymous due to their jobs, the five have not been arrested or charged for their attack on the staff and the damage done to Crossroads.

Some staff sustained minor injuries in the attack, such as bruising, Chafee said. Only one staffer needed to be medically treated offsite and no youth needed to be medically treated offsite, he said.

To make up for the cancellation of school and other programs due to COVID-19 protocols, ACS has said it is offering a variety of options. They are offering virtual programming, such as a writing program, poetry, yoga and other activities. Although in-person visits have been suspended during the pandemic, video visits are available for family and lawyers. The youth are also allowed to write letters.

Marco Poggio

Derrick Haynes, retired from being a guard at Horizon Juvenile Center, believes there’s only one way to control the coronavirus within the youth detention facilities.

Now-retired Horizon guard Derrick Haynes said what needs to happen to ensure the safety of the staff and the youth is to “slow things down.” The mayor and the governor need to work with the district attorneys’ offices to figure out how to release most of the youths with ankle bracelets and supervision, he said. He would seek permission from supervision to slow things down in the facility “to a crawl.”

Short of that, he said, ACS should let the staff put the youth in mandatory room confinement. It’s what he would do in the wake of a violent outbreak. Everyone would get one hour of recreation by themselves. Meals and medicine would be delivered to each room.

“Either you let the kids out or you put them in mandatory room confinement,” Haynes said. “It's the only way you can isolate those kids; they can only come out one at a time. It’s the only way to ensure that you don’t spread the virus.”

“They're going to abandon their post,” Haynes said. “Anybody with any sense would. ‘I'm going to abandon my post and go call supervision.’ You have to let those kids out one at a time.”If all the youth were in the hall at the same time, all they would have to do would be to take off their masks and start coughing and the staff would be forced to leave, he said.

But for that to happen Gov. Andrew Cuomo would need to intervene and temporarily lift restrictions on solitary confinement for youth.

“That's bigger than the city, that's the governor,” Robinson said. “Remember, this is the governor's baby — raise the age — so that's why I'm saying those are legislative issues that we have, not city issues.”

This story has been updated.

Pingback: New York COVID-19 in detention - World Peace Foundation