Now that every state has passed laws to raise the age at which youth can be automatically shifted to adult court and facilities, isn’t there some cause for a relaxation of efforts to upend the juvenile justice system?

And, with 40 states and Washington, D.C. changing more than 100 laws to limit juveniles in the adult system, where’s the celebration? At the federal level, with the Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act being reauthorized after 25 years and the Prison Rape Elimination Act passed, surely advocates should be satisfied.

Marcy Mistrett

Marcy Mistrett is having none of that.

“RTA is a critical step in preserving childhood for the vast majority of children who come in contact with the law,” said Mistrett, the executive director of Campaign for Youth Justice. "However, raise the age doesn’t touch the states’ transfer laws.”

Nor does it impact the school-to-prison pipeline, erase the racial imbalance of the system or effectively stop entry of juveniles into the system by diverting them into alternative programs. And a new movement wants to include detained youth in the reparations debate, according to Tyler Whittenberg, chief counsel for justice systems reform at the Southern Coalition for Social Justice.

Across the country, the juvenile justice advocacy movement is far from sitting still.

"It's not like we're not done yet,” said Liz Ryan, president of the Youth First Initiative in Washington, D.C. In North Carolina, for instance, 45% of all juvenile complaints were school-based, and 48% of those complaints were against black students between July 2018 and June 2019.

Liz Ryan

Ryan listed action items: further reduce youth involvement in court; correct the racial bias in policing, arrests, detentions and transfers to adult court; decrease or eliminate the involvement of a probation system that, according to advocates, catches minors for small things and sends them back into court and, possibly, jail or prison; and scale up the volume of community alternatives for youth while ending the criminalization of poverty by, for one, eliminating many fees and fines for youth.

The list is long. But, “it's not like there's a sequential list of reforms that people are doing in a specific order,” she said. “We're not done getting kids out of court, although that's been dramatically reduced. We're not done getting rid of incarceration.”

Just take racial inequity. In 2010, black youth were 10 times more likely to get an adult sentence than white youth, Mistrett said. That has dropped significantly since then, along with a massive slide in juvenile crime and the corresponding juvenile lockup rates, she said.

But still, about 66% of locked-up juveniles are youth of color, according to the National Conference of State Legislators.

And 88% of juveniles in the adult system are youth of color and about 4% are LGBTQ or gender nonconforming, according to the Campaign for Youth Justice.

“Definitely still disgusting,” Mistrett said, "but moving in the right direction.”

Automatic transfers

The mission of the Campaign for Youth Justice is grand but to the point: to end the practice of prosecuting, incarcerating and sentencing youth under 18 as adults. Its anchor campaign is to remove youth already in adult jails and prisons, and to end or, at least reduce, automatic transfers of youth to adult court for certain charges.

Mistrett gave the following example to show the system is nowhere close to halting automatic transfers, or even slowing them: Alabama led with 1,200 transfers in 2017, then Florida with 1,169 (2018), Maryland with nearly 700 (2016), Pennsylvania with about 475 (2017) and Nebraska with 265 (2017). The years indicate the year in which the transfers took place. And the totals don’t include the eight states still in the process of implementing raise the age laws. (North Carolina, the last state to pass such a law in summer 2017, finally implemented RTA in December.)

Gains have been made in the organization’s 15 years. A 70% drop in youth charged as adults to the current level of about 76,000, according to the campaign’s April report, and a drop of 48% in the number of youth in adult jails or prisons since 2005. Also, 70% of youth charged as adults, according to the report, are now held in youth detention centers.

Southern Coalition for Social Justice

.

Many states have waged efforts to shutter youth prisons altogether. Some, including Vermont and South Dakota, have been successful, while others, including New York, have moved to “closer-to-home” policies that entail closing down large facilities to create more therapeutic approaches for youth. California and Texas have closed large facilities, but advocates argue they traded the warehouse-type of detention for smaller, more local prisons — but prisons, nonetheless. Washington, D.C., has taken a similar approach, closing a large prison and creating a smaller center for minors.

According to Mistrett, shifting some minors back to youth facilities can have a big influence on troubled youth in detention because they’re people to look up to.

“These people are like [role] models,” she said. “They’re a little bit older, they get the system, they get the programming, they can help calm the younger kids down. They're like, you know, they want to stay there as long as possible because they know what the alternative is. And they really want to show that they can turn their lives around.”

But too often, Mistrett and others say, society, law enforcement and the staff of juvenile facilities view youth under their watch as “monsters, animalistic … And the other thing around all of this is, when we see a black child or a Latino child with a gun, any sense of childhood gets thrown out, and any concept of childhood gets thrown out of the window. They’re assumed to be so bad.”

And so, the cycle continues of young people getting into trouble in school, which draws in police, who arrest them, giving them a record. And, if not diverted to a community or some other alternative program, or teen court, these youth can end up in detention.

“A whole menu of things has been done,” Mistrett said. “[But] whether it's draining the flow going in [detention] on the front end, or keeping kids out on the back end, there’s a whole menu of things that are still being pursued.”

Ryan agrees much more work needs to be done, including on raise the age. While New York and North Carolina became the last states to lower the age of youth from 18, some states, she said, need to act on getting rid of the 17-year-old cutoff.

“They were the last to raise the age to any automatic prosecution of all 16- and 17-year-olds,” she said of New York and North Carolina. “Wisconsin, Texas and Georgia still automatically prosecute all 17-year-olds.”

Also, there’s no national uniformity in terms of who signs off on the transfer from juvenile to adult jurisdiction. In some states, it’s the prosecutor’s office that decides; in others, it’s a judge. And it depends on the charge. There is no uniformity there, as some states, including North Carolina, automatically transfer depending on the severity of the charge — such as murder or sexual assault.

So, there are exceptions to the raise the age laws that advocates believe need to be erased.

“We’re shutting the door, but it isn’t quite all the way shut,” Ryan said. “That’s still on the agenda of things that are being worked on. In some states, they need to really narrow that door even more — as much as possible.”

Asked if that door could ever be shut, Ryan said, “I think so,” pointing to opinion polls showing people are in favor of more treatment over harsh penalties for juveniles.

For example, in a March 2019 poll of 1,000 people commissioned by Youth First Initiative, 80% supported providing “financial incentives for states and municipalities to invest in alternatives to youth incarceration, such as intensive rehabilitation, education, job training, community services, and programs that provide youth the opportunity to repair harm to victims and communities.”

Reparations

Whittenberg echoed that the advocacy movement still has plenty on its plate.

“Raising the age represents a move in the right direction,” he said. "However, North Carolina and states throughout the U.S. continue to funnel students of color, LGBTQIA+ youth and children with disabilities into the justice system at disproportionate rates. Each instance of youth criminalization causes severe and lasting harms on the individual, their families and the communities in which they live. Raising the age helps ensure fewer youth are exposed to the adult justice system, but does nothing to address the trauma experienced by youth who are currently forced into the courtrooms and cages of today’s juvenile justice system.”

Tyler Whittenberg

In North Carolina, Whittenberg said, the "next step should be ending school-based arrests and referrals to law enforcement ... For many students of color, school feels more like a doorway to the justice system than a place of learning and support.”

He would like to see state efforts go further — much further. He is working to take the movement in the direction of reparations — including youth in the broader national discussion over what is due to the people of color who are oppressed, killed, wrongfully jailed and imprisoned or jailed at rates far higher than they represent in the general population.

Whittenberg is based in North Carolina, which implemented raise the age last December after more than a decade of trying to pass it into law. By fully putting the law in place, North Carolina is now ahead of some peer states where raise the age laws have not yet been fully implemented.

“If you are marching toward ending the juvenile justice system — if that’s not where you’re headed, you’re going the wrong way — much of that work has been done,” Whittenberg said. "I would argue that we really need to have the courage to start thinking about reparations for the youth who have been criminalized for age-appropriate behaviors, who were then forwarded to the adult system.

“The aim for many years [of raise the age] has already been done,” he said. But there is not retroactivity under RTA laws, so many minors incarcerated under old laws will remain in adult facilities.

“What does reparations look like for these students who have to leave you and their families, who have already been impacted by laws that we know to be archaic and harmful to communities of color,” Whittenberg asked.

Marion Humphrey Jr., a research and policy legal fellow at the Campaign for Youth Justice, also raised the issue of reparations in a post on CYJ’s website:

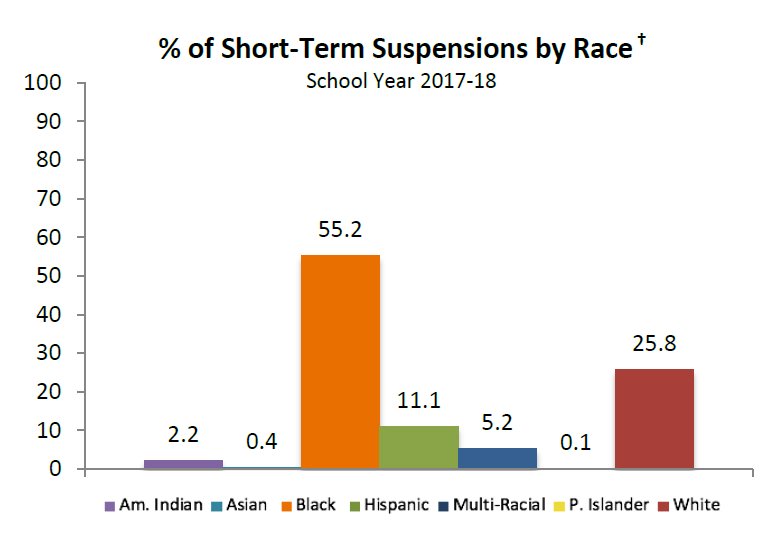

"This conversation about criminal justice disparities and reparations often fails to highlight outcomes for youth in the adult criminal justice system. Research indicates that even when accounting for the type of offense, Black youth are more likely to be sent to adult prison and receive longer sentences. And while Black youth represent approximately 14% of the total youth population, as of 2017 they comprise 54.2% of the youth who are transferred to adult courts by juvenile court judges who believe that juvenile courts cannot serve them effectively. Black youth are 72% of the children who have received life in prison without parole since the Supreme Court’s decision in Miller.”

So while raise the age was a massive step for many advocates, a long road still lies ahead.

This story has been updated.

Why was no conflicting view presented here? Have you presented it in another article perhaps? If so, a reference should be included. Why also, just a raw listing of statistics; as though, that in itself means the “system is biased”? Incarceration rates could be a result of actual desert rather than just “systemic racism”; yet, there’s NOTHING in this article that tests premises. This article as seriously biased toward conclusions rather than news.