As North Carolina began to send 16- and 17-year-olds to its juvenile justice system for the first time, year one was meant to be instructive. Starting in December, the influx of an older set of defendants — an annual cohort expected to number 8,673 — would require an expansion of the system. More judges, prosecutors, court counselors and defense attorneys. More vans and drivers to shuttle youths from their detention facilities to courthouses and back. More beds.

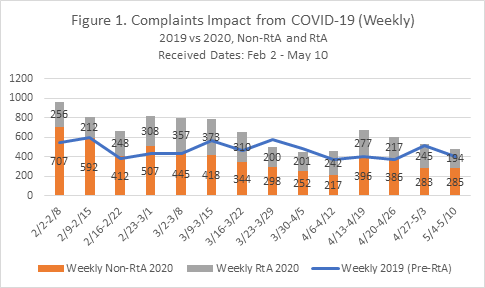

As 2020 started to unfold, stakeholders on all sides tracked the numbers of complaints, preadjudication detentions and post-adjudication confinements to see how closely they matched the projections laid out in a January report by the state’s Juvenile Jurisdiction Advisory Committee (JJAC), which is tasked with planning the implementation of raise the age.

Then, in February, COVID-19 hit.

“We were just sort of getting in the groove of raise the age,” said Eric Zogry, North Carolina's juvenile defender and a JJAC member. “The courts were, rightfully so, limited in the kinds of cases that could be considered. And on top of that, school’s out.”

Every year, about 45% of juvenile complaints in North Carolina originate from incidents that happen in schools. Gov. Roy Cooper ordered schools to close statewide on March 14, and his general stay-at-home order followed two weeks later. These measures — in theory, at least — would prevent encounters between friends and foes alike.

Every year, about 45% of juvenile complaints in North Carolina originate from incidents that happen in schools. Gov. Roy Cooper ordered schools to close statewide on March 14, and his general stay-at-home order followed two weeks later. These measures — in theory, at least — would prevent encounters between friends and foes alike.

By late March, juvenile courts were seeing far fewer complaints than expected. Youth detentions for the year were lower than projected.

Last year, in the third week of March, juvenile courts received 600 complaints involving youth under age 16. In the same week of 2020, the courts saw just under 300 such complaints, plus an additional 200 from youths age 16 or 17.

Those are summer numbers, said a spokesperson with the North Carolina Department of Public Safety’s Juvenile Justice division.

Before coronavirus, the division was expecting the larger cohort to draw more complaints. But for two weeks the expanded, post-raise the age cohort drew fewer complaints in 2020 than the smaller 15-and-under set did in 2019, according to figures provided by DPS.

North Carolina Department of Public Safety

.

But the coronavirus doldrums didn’t last. In mid-April, the numbers shot up again, aligning closely with projections, before dipping again as April turned into May. (Considering there’s typically a 30-day lag between when an incident occurs and a juvenile complaint is filed, it’s unclear how much of the initial dip was because of the slowdown in the juvenile courts, according to Zogry.)

Overall for calendar 2020, misdemeanor complaints are lower than projected. Youth status offenses such as truancy and runaways, which applied to all those under 18 even before raise the age went into effect in December, are down 24%.

But serious offenses — the A- through G-level felonies that often land youth in juvenile detention pretrial and in North Carolina’s adult criminal justice system — aligned with DPS’ predictions for the year even through March, when schools shut down. For the month of April, serious offense complaints shot past projections by 20%, with 66 juveniles receiving A- through G-level felony complaints compared to 55 expected.

Also scrambling North Carolina’s raise the age predictions is that a significant portion of the state’s youth in custody were released as coronavirus spread throughout the U.S. By mid-April DPS had released about 25% of the youth held in detention centers before their adjudication and about 10% of those serving juvenile sentences in youth development facilities.

DPS spokeswoman Diana Kees said that with the advent of coronavirus, the department’s primary focus has been preparing for imminent threat to the health and safety of workers and detained youth, and that the virus has hastened the adoption of videoconferencing for visitations, telemedicine and hearings. But it’s also engendered some confusion during the inaugural year of raise the age.

“Implementing RTA during the coronavirus pandemic has made it difficult to know if the rate of complaints being filed is a true reflection of the capacity that is needed by the system moving forward,” Kees said.

More beds, judges, staff needed?

North Carolina’s Juvenile Justice section created its raise the age projections by combining juvenile justice data with confinement and supervision data from adult corrections, charge data from the Administrative Office of the Courts and conviction data from the state’s Sentencing and Policy Advisory Commission.

The JJAC reported in January that, in addition to the 43 new beds the state had already created for juveniles held in custody preadjudication, an additional 185 beds might be needed to accommodate the 16- and 17-year-olds.

Will the state, which has beds for 233 youth held preadjudication, need to house 418 as predicted and planned? The committee’s report recommends $3.7 million in capital spending on new detention beds for fiscal 2021.

Only 73% of the projected number of youths were admitted to juvenile detention in April 2020, according to DPS.

Will North Carolina’s juvenile system need the additional judges that JJAC projects it will need after 2021? Will it need the 100-plus additional prosecution staff that the Administrative Office of the Courts anticipates it will need by 2023?

The coronavirus-induced fluctuations in complaint numbers make it “hard to make resource decisions,” Zogry said.

“By the end of April, we were going to kind of see what it really looked like based on [DPS’] projections, but that never happened.”