![]() If you’re still following along in this series on the problems with plea bargaining in the juvenile justice system, then hopefully you agree that plea bargaining should be eliminated or substantially modified in how it’s applied. Or maybe you’re still vacillating and hanging around to see if I say something that may push you off the fence one way or the other.

If you’re still following along in this series on the problems with plea bargaining in the juvenile justice system, then hopefully you agree that plea bargaining should be eliminated or substantially modified in how it’s applied. Or maybe you’re still vacillating and hanging around to see if I say something that may push you off the fence one way or the other.

Judge Steven C. Teske

Or, you think this idea is a bunch of crap, and I am crazy for bringing it up. Maybe I am crazy, but it’s a “good crazy,” which sometimes will eventually become the norm. It was Bertrand Russell who said, “Do not fear to be eccentric in opinion, for every opinion now accepted was once eccentric.”

This column is my last attempt to win the skeptics over before I jump into the art and science of how to transition to a non-negotiating juvenile justice system. I will repeat myself somewhat, but to avoid redundancy, I will change up my delivery and use a different approach, a systems model, to explain the contrariness of plea bargaining in the juvenile court.

For more information on Evidence-Based Practices, go to JJIE Resource Hub | Evidence-Based Practices

I will also offer some balance to evidence-based practices and programs (EBPs) to caution folks that EBPs are not the silver bullet to reduce recidivism. They are important, and I maintain are required, but not the cure-all. I will talk about what forces are working against EBPs producing at their optimum capacity or working at all, and some strategies to offset those forces.

I offer caution respecting how we apply EBPs and how our failure to do EBPs with fidelity is harmful to youth. Quite frankly, if we don’t get it right, the kids may be better off not being exposed to them at all. And a major contributor to this fidelity issue are the many providers offering EBPs, making a profit and not delivering the goods with fidelity.

Just to be clear, I am a believer in EBPs, but they are not the only thing served on my plate of rehabilitation. Irrespective of my cautions, it doesn’t change the fact that plea bargaining is contrary to EBPs when done correctly.

What works, what doesn’t can’t occupy same space

For those vacillating, there is not much to offer beyond the last column. I wish there were, but there isn’t. But, give me a moment to take one last shot. For the “believers,” consider this a refresher, but described using a different approach and tack.

Systems theory in political science (which I applied in my thesis work for my master’s in political science) is helpful to understanding why plea bargaining — one method of deciding a kid’s outcome in court — cannot occupy the same space along with evidence-based tools — another means of decision-making. There is one exception: Any part of either or both practices that is not in conflict may co-habit the same space to achieve the desired goal. More specifically, any parts or stages of plea bargaining that don’t shape or form the ultimate disposition may remain intact and included in the guilt-innocence process.

An example would include limiting the plea bargaining to negotiating the charges without any recommendations for what could happen at disposition. In other words, the state’s motivation to dismiss or merge offenses is to encourage the juvenile defendant to admit to fewer offenses and thus avoid a time-consuming trial, which is one of the benefits of plea bargaining. However, what to do in response to the youth’s delinquent act is bifurcated at a separate hearing (i.e. disposition hearing) to allow the time needed for the youth to be evaluated, his risk and needs assessed, and a recommendation prepared that is grounded on the findings of the assessment tools.

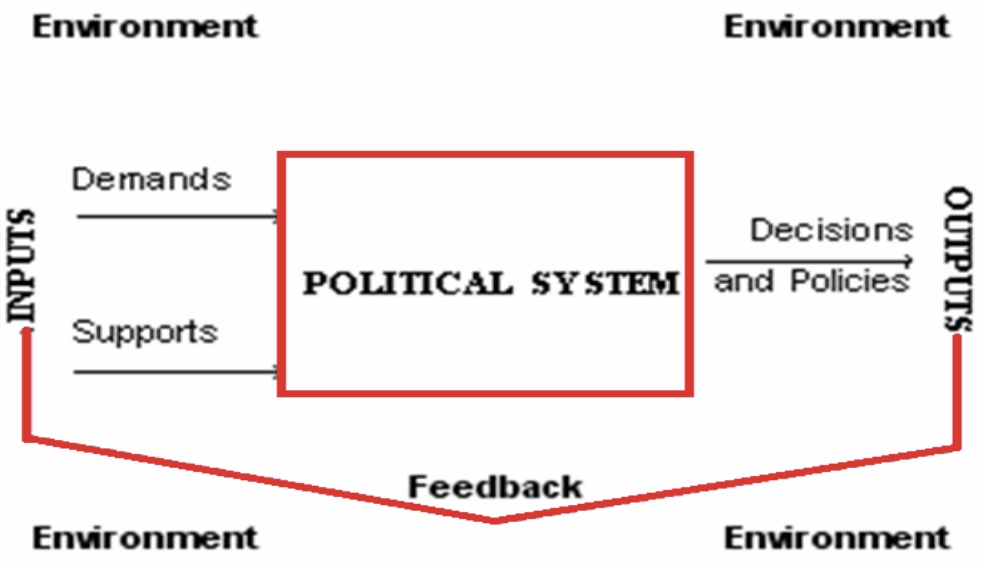

The systems model approach, which is shown below, informs us that systems, which include juvenile justice, are influenced by changes in the social or physical environment surrounding that system. That in turn produces "demands" and "supports" for action or the status quo directed as "inputs" toward the system that may be political, legal or social in nature. Take, for example, the rising juvenile crime rates in the ’80s and early ’90s that led to the “superpredator” scare among the public. This scare led to a public outcry that resulted in demands on the system to protect the public from these “superpredator” kids.

“A Systems Analysis of Political Life,” David Easton

.

These demands and supporting groups stimulate action in a system, leading to decisions or outputs directed at some aspect of the surrounding social or physical environment. These demands for protection from “superpredator” kids led to decision-making that produced outcomes that included the passage of “get gough” laws that in turn incarcerated more kids that in turn led to building more prisons.

When a new policy (i.e. outputs) interacts with the environment (citizens, other agencies, budgets, etc.), the policy may generate new demands or supports. These new demands and supports work to influence and shape the policy, and thus the cycle is never-ending.

For example, the next decade (2000s) brought us new demands and supports in the form of adolescent brain research and the “what works” research literature describing the types of evidence-based programs proving more effective to reduce recidivism compared to incarceration generally. As a direct result of the teen brain science, the U.S. Supreme Court banned the execution of kids and life sentences without the possibility of parole.

Consequently, local and state juvenile justice systems started a trend to reform their policies by deinstitutionalizing youth by relying more on community-based solutions. In recent years, we are witnessing a gradual dismantling of the “get tough” practices in local communities, such as mine, and among several states, including my own. Whether this trend will continue remains unknown, but gives some of us, like me, hope.

By applying the systems model to whether plea bargaining is operable in an evidence-based system, we must begin by identifying the demands that would influence the creation of a policy to eliminate plea bargaining, or at least modifying its form so that parts of plea bargaining may cohabitate with an evidence-based process.

Spread of brain science

We can readily identify the demands by looking at the growing number of courts that have embraced the teen brain science as well as the “what works” studies, and in so doing have made drastic shifts in how to approach the treatment of delinquent youth.

The courts that have embraced the teen brain science have incorporated EBPs, such as objective assessments tools to help decide if a kid should be detained upon arrest, risk and needs tools to guide the court in deciding how to respond to the kid’s delinquent conduct, graduated sanctions programs that allow for probation officers to quickly respond to a kid’s violation of a technical condition and replacing incarceration with effective community-based solutions like functional family therapy, multisystemic therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, moral reconation therapy, seven challenges drug treatment and more.

This overwhelming evidence of what works better to treat delinquent kids has become somewhat infectious. We are witnessing governors, both Republican and Democrat, seize on this irrefutable evidence to reform their entire statewide juvenile justice system.

In 2012, for example, then-Georgia Gov. Nathan Deal appointed me to his Criminal Justice Reform Council to assist in bringing these evidence-based practices and programs to our state. Gov. Deal was strategic to create a diverse and collaborative body. He also recruited the expertise of the Pew Charitable Trusts to help us break down and analyze our juvenile justice data as well as understand the evidence-based practices and programs.

Our recommendations were unanimously approved by a legislature overwhelmingly Republican, and not historically known to be friendly to counter-intuitive approaches that don’t look tough on crime. I am confident the sweeping changes were accepted largely because the process was transparent (i.e., politically bipartisan, collaboratively diverse and grounded in empirically proven studies that strongly supported the recommendations). Other states have jumped on the reform bandwagon like Kentucky, Hawaii, West Virginia, Tennessee, Kansas and South Dakota, just to name a few.

And let’s not forget how Massachusetts, Illinois, Connecticut, North Carolina, South Carolina, Louisiana and New York were influenced by the teen brain science to raise the age of adult criminal liability from age 16 to 18. Legislation to raise the age in my state of Georgia has been filed and will be debated. We are experiencing pretty much the same issues as the others: The majority agree on the moral reasons to raise the age but worry about costs irrespective of the fact that our sister states have shown that the exorbitant costs they feared were imagined, not real.

Significant and often overlooked support comes from the community. Believe it or not, Republican and Democrat voters alike have supported these reforms, according to surveys of voters conducted by Pew Charitable Trusts. They concluded from these surveys that, “When it comes to the juvenile justice system, voters want offending youth to get the services and supervision they need to change their behavior and stop committing crimes—even if that means less incarceration.”

One would think that governors, legislators, and judges would enact reforms supported by the public. Why? Because positive outcomes get us re-elected!

But how does all this affect the role plea bargaining has in juvenile courts?

Answer: If we (judges, court administration, and other system stakeholders) are paying attention to the environment around us, we would recognize that the demands and supports inform us to act to deinstitutionalize youth by employing EBPs. But to implement EBPs with fidelity, it must occur post-adjudication when the youth is not constrained by his right against self-incrimination and is therefore free to share, and truthfully, about his circumstances.

Plea bargaining and EBPs can’t occupy the same space because risk and needs assessments are designed for the disposition hearing whereas plea bargaining occurs before disposition at the adjudication stage. Plea bargaining usually begins with the prosecutor making an offer of disposition to the youth that will entice the youth to admit and forgo a trial. But whatever offer made will not include the recommendations of the risk and needs assessment because the youth’s right to remain silent precludes sharing the information required to complete the assessment.

Having a conversation about what’s best for the kid before acquiring the information needed to know what’s best is a waste of time. And when what we’re doing is a waste of time, it’s most likely harmful to the kid and to the community. When we don’t improve the behaviors of the kid, we increase the risk to the community. It would be like keeping a doctor from diagnosing an infectious disease: We not only risk the patient’s death, but the death of potential millions who would become infected.

I have talked a great deal about the importance of EBPs, but I have a word of caution about embracing EBPs without acknowledging the other practices or considerations that are not on the “what works” list, but are equally important. Without these other practices or considerations, the effectiveness of EBPs are diluted, or not effective at all, and thus a waste of taxpayer money.

The ‘what works creep’: what they’re not telling you

My word of caution begins with understanding the difference between evidence-based practices and evidence-based programs. They are not synonymous, but they share the empirical studies that show why a certain practice is effective and why a certain program is effective. Despite the differences between practices and programs, they work in tandem to reduce the risk of reoffending.

For example, detention assessment tools are a practice to prevent the kids who make us mad from entering the detention facility.

Why? Because we know the empirical evidence shows that the use of detention on low-risk, nonviolent kids will make them worse.

[Related: The Contrariness of Plea Bargaining in Juvenile Courts]

[Related: Plea Bargaining Hurts Both Guilty and Innocent Kids]

[Related: To Use Evidence-based Programs For Kids, Get the Lawyers Out of Here!]

Diversion is a practice that utilizes alternatives to prevent the kids who make us mad from going deeper into the justice system.

Why? Because we know from empirical studies that most kids will age out of their delinquent conduct, and that other studies show that overtreating them increases the risk they will graduate to a kid who scares us.

Risk and needs assessments are a practice used at the disposition stage to assess criminogenic needs for the purpose of identifying what programs are best suited to respond to each criminogenic need.

Why? Because the empirical studies inform us of the underlying causes (criminogenic need) of delinquent behaviors so we can match evidence-based programs to each criminogenic cause.

But Functional Family Therapy (FFT) and Multisystemic Therapy (MST), to name a couple, are programs, not practices, because they deliver direct services to youth that can rehabilitate the anti-social behaviors.

But what the many profit-making manufacturers of these evidence-based programs do not share with us is that EBPs are not the magic bullet that will save our youth. They would have us believe that all we need do is purchase their program and our youth will do better.

Demands of poverty

Baloney. That is complete and unadulterated horse manure. EBPs are a necessary factor in the equation of recidivist reduction, but it’s not the only equative factor. This is because the EBPs, mostly the “program” side, competes against the structural social conditions that most of our youth confront daily, the pains, suffering and stress associated with poverty.

It’s the Maslow’s hierarchy of needs thing. How do we get kids to focus on treatment when they go home and watch everything around them go to hell in a handbasket? They’re struggling daily with home, food, clothing and many other insecurities yet we expect them to seek higher ground and be true to our technical conditions of probation and adhere to the teachings, instructions and counseling they receive through cognitive behavioral therapy, moral reconation therapy and other EBPs.

We’re fooling ourselves to the point that we insult them while also embarrassing ourselves. The sad irony is that poor folks do feel insulted by our lack of common sense in not figuring out that many of the practices we employ criminalizes them deeper into the system and makes matters worse, for them and for us.

Sadly, our implicit biases check our common sense at the door: Thus we can’t separate the trees from the forest, what works and what doesn’t, and what’s morally good and not. What’s sadder is that poor folks know we should be embarrassed by our shameful practices, but our pride coupled with our ignorance is too strong to feel embarrassed.

I know because I had one of these poor folks shame me just after I took the bench. It was in the early days before expanding diversion and implementing objective assessment tools. Arraignment calendars were large, and the courtroom was packed, standing room only.

I had just entered the courtroom and sat down when I overheard a black mother sitting in the front row tell her son how the system was racist. I felt her statement was ridiculous and asked her why she thought we were racist. Without hesitation, she waved her arm across the courtroom full of black kids sitting with their parents and said, “Look for yourself!”

Like many of us, I personalized her comment and made it about me. I let what she said rent space in my head. My implicit bias gave me tunnel vision. What she was pointing out to her son was right in front of my eyes, but my bias coupled with my oversensitivity blinded me.

With one wave of her arm, this uneducated mother expressed her thoughts poignantly and delivered a teaching moment to me.

I did figure it out: The overwhelming number of kids in the courtroom that day had no business being there. We were criminalizing adolescent behaviors by using zero tolerance policies in the schools and over-reacting to behaviors in the homes and on the streets. Thanks to our expanded diversion system and use of assessment tools to keep kids out of detention, we don’t have arraignment calendars anymore because we don’t arrest students and we divert most delinquent cases. We do arraignments, but on a case-by-case basis peppered here and there on a delinquent docket.

We need to decarcerate

And therefore the “practices” side of what is evidence-based is beneficial. The circumstances of poverty are bad enough, but anything we can do to avoid aggravating those circumstances is essential. One of the major steps to end poverty is to create a system of decarceration as opposed to incarceration of our poor families. It starts with evidence-based practices including the expansion of diversion programs, creating objective detention admission assessments, risk and assessment tools to minimize the commitment of youth to state custody and dismantling the school-to-prison pipeline.

Too many kids of color are trapped in poverty, and many of our laws keep them trapped. And irrespective of the fact that poverty makes doing our rehabilitative work difficult, there is no reason we can’t create those evidence-based practices described above to stop the criminalizing of poor kids. How sad that poverty places them behind the eight ball, but how cruel that we crush them with it by not taking the steps to close our juvenile court doors to stop the criminalizing of poverty.

By implementing these practices in Clayton County, Ga., the number of black youths detained has declined by 63%; the number black youth committed to state custody has decreased by 68% and the number of black students arrested on campus has fallen 91%.

In his book, “Not a Crime to Be Poor: The Criminalization of Poverty in America,” Georgetown University Law Center’s professor Peter Edelman describes how justice systems criminalize the poor, and specifically cites the Clayton County juvenile justice system as a model for decriminalizing youth, noting, “It is not surprising that Clayton County and Teske are regarded as national models.”

But the “programs” side of what is evidence-based is a different story, and one best shared by a former probationer named Will.

Will was once deep in the gang life, but today a college graduate working on his master’s. He graduated from my Second Chance Program, which is dedicated to the higher of the high-risk kids. On occasion, Will travels with me to share his story of transformation. He is one who praises the evidence-based programs he was in while on probation, but he also admonishes practitioners to consider how the circumstances of poverty dilutes the degree of meaningful responsivity to the program.

“It felt good to put $400 in my mom’s hands every month to help her pay the rent,” Will explained.

He described how the family was evicted repeatedly and his more affluent peers harassed and bullied him for the hand-me-down clothes, having no means of transportation and going some mornings and nights without food.

An old friend from elementary school offered him a way to make money, by joining his gang. He started robbing folks and breaking into homes.

Relationships broke the cycle

“Desperate kids do desperate things,” he told a group of judges in San Diego.

He counseled them, saying, “Unless you help families figure out how to cope with poverty, your programs will not stop us from doing what we feel we need to escape poverty.”

A judge piped up and asked him how he escaped the daily issues with poverty. Will answered, “The program was family-focused and centered on building relationships between the judges, probation officers, and other staff and my entire family.” He added that “They wanted to know about every struggle we faced so they could help us figure out ways to overcome them.”

Will made it very clear that what we did for his family didn’t deliver them from poverty, but it taught them how to cope with crisis, which lessened the stress and didn’t put him in a place to take flight, freeze or fight. “That’s how I muddled through safely,” he said.

“And it allowed me to break the cycle of poverty for my family,” he concluded.

A couple of notes of caution respecting risk and needs assessments. These tools are not prescriptive. They are not, in that black and white sense, intended to prescribe what the court must do with the kid, but they frame for the judge the most relevant and effective guide for making the best decision for that youth and ultimately the safety of the community.

The other warning is to limit their use to adjudicated youth considered for probation or commitment, but not for use at the front door to decide diversion. The front door decision-making is a different creature and should involve a different system to decide what cases don’t go to court.

Applying a risk and needs assessment at the front door increases sucking low-risk kids with high needs into the system under the guise that they need services. Maybe they do, but not in the delinquency system. We should avoid net-widening practices to allow our kids to age out of delinquency through normal adolescent development.

I call this phenomenon the “what works creep,” or when the system overuses evidence-based practices by allowing, for example, tools designed for kids who need supervision to be used on kids who are first-time offenders on a misdemeanor offense. This “creep” begins with the notion that, “Hey, why not use these tools with all the kids and see what’s going on with them?”

Gee, I wonder what could go wrong with that idea?

When we do the “what works creep,” probation caseloads will increase. What starts out as an idea to make the kid better turns out making the kid worse. And the flip side is that flooding caseloads with low risk youth dilutes the supervision intensity needed for high=risk youth.

Programs not enough without services

There are evidence-based practices (objective admission tools, risk and needs assessments, diversion, graduated sanctions, etc.) and evidence-based programs (FFT, MST, etc.). The practices focus on the means to identify youth appropriate for detention, probation or commitment, criminogenic needs to assign treatment, and divert from the court. The programs focus on direct services to interrupt the anti-social thinking and conduct of the youth.

The programs side of what’s evidence-based are not magic bullets to reduce recidivism despite what some for-profit manufacturers would have us believe. But delivering these programs doesn’t come easy, and what they don’t tell us is that why they’re difficult has a lot to do with the social structural conditions facing our kids every day, and I am speaking about poverty for the most part.

If poverty is a serious driver of crime, then it begs the question of how evidence-based programs remove the stressors of poverty. I get it that these programs are designed to help kids think in pro-social ways so they can formulate better decisions, but they still must endure the stress and pains of their economic insecurities that continue to push them to act in anti-social ways just to get by.

We must include the type of wrap-around services for the kid and his entire family that are effective in providing our poor families with the coping skills and services to lessen their stressors. If Will’s mother had not received the assistance she needed to stop the evictions, do we really believe that Will would have stopped the robbing? Do we really believe that evidence-based programs are that good to ward off the daily sufferings of poverty that influence poor judgments leading to theft and a gang lifestyle? Just because a kid would like to stop stealing doesn’t mean he will unless the need to steal is eliminated, and I maintain that EBPs alone are not enough.

Many of our poor kids are better off if we implement the practices side of what is evidence-based, which will divert them from our juvenile courts or keep them from being removed from their families. It may not save them from poverty, but it certainly prevents criminalizing our poor and aggravating their circumstances, and thus keeping them trapped in poverty indefinitely.

In the next column, we will discuss how to transition from a plea-bargaining system to an evidence-based system that works using a procedural fairness model for reform.