NEW YORK — While working as a monitor in the dean’s office her freshman year of high school, Alexis Lanysse spent most of her time filing papers and signing late passes. But she sometimes had another task: She’d log onto Facebook or Snapchat to track incidents that the dean’s office would investigate.

The office at the Brooklyn high school would use the evidence to help decide how they punished students. Sometimes they handed out suspensions and mandated transfers. Once, her school called a group of monitors to track a Snapchat story of a student getting shoved into a locker. The story was reposted several times, and the student monitors were told to track the post to find who originally filmed it.

“It didn’t really register how insane that is, to have teachers asking to go in your personal social media account and look for things,” Lanysse said.

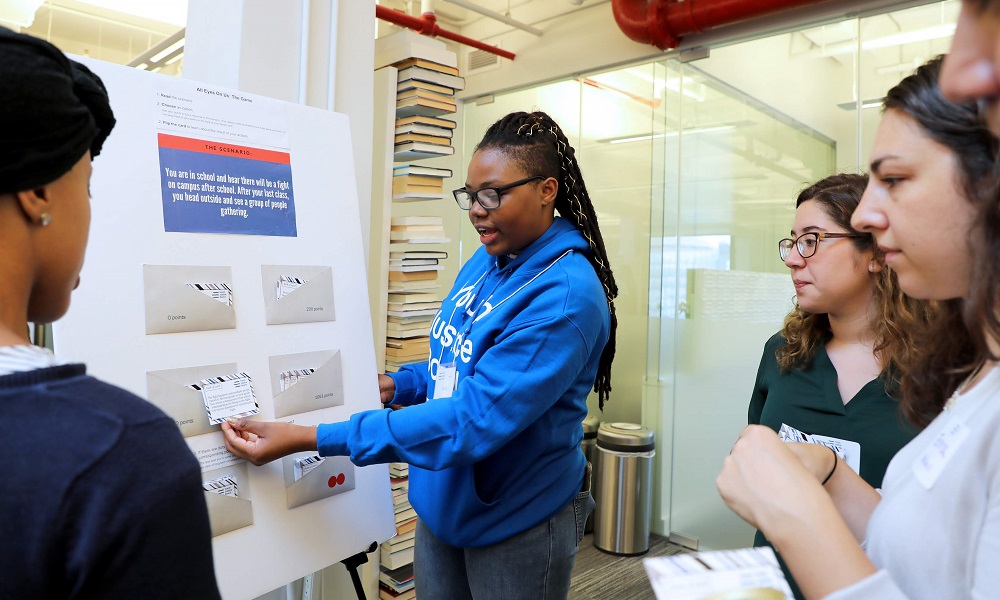

Three years later, a report that Lanysse, now 17, researched as part of the Youth Justice Board, a teenage-led after-school policy initiative, sheds light on the unregulated, largely private digital surveillance system used by several city agencies. It found that people in the parts of New York City with the heaviest amount of surveillance often have little to no education on how to use social media — and that the surveillance system disproportionately criminalizes youth of color.

Three years later, a report that Lanysse, now 17, researched as part of the Youth Justice Board, a teenage-led after-school policy initiative, sheds light on the unregulated, largely private digital surveillance system used by several city agencies. It found that people in the parts of New York City with the heaviest amount of surveillance often have little to no education on how to use social media — and that the surveillance system disproportionately criminalizes youth of color.

The All Eyes on Us report lays out eight policy recommendations meant to help regulate and disclose now-private information about surveillance in New York City schools and the New York Police Department: a more accessible digital citizenship curriculum in city schools; restructuring or eliminating the city’s gang database, a list of potential gang members that is 99% comprised of people of color; and enhanced oversight for how city agencies can use social media for surveillance purposes.

‘Digital-savvy divide’

The report gives a glimpse into how teenagers with the least amount of digital training are often monitored the most heavily. The New York State Department of Education categorizes “digital citizenship” skills in its library curriculum — which is separate from the state’s standardized curriculum. But not all schools have sufficient resources for nonstandardized curriculum. In Harlem, 87% of the public schools do not have sufficient library staff to meet state regulations, the report said.

The Youth Justice Board recommended that the state Department of Education include digital citizenship in its social studies curriculum. It also urged adding a conflict response curriculum starting in kindergarten. Internet conflicts stem from personal conflicts, the report said, and the punishment system rarely fixes the root of each conflict.

“By leaving digital citizenship and rights out of a standardized education, both the state’s Education Department and the city’s Department of Education allow the digital divide to mutate into a digital-savvy divide,” the report said.

The report paints a picture of the “digital-savvy divide,” an education gap that leads to many students first learning about social media policy when they’re punished for violating it.

One student was suspended after he alerted his friend to a snap from a classmate. The classmate wanted to fight his friend. His friend’s parents called administrators. But the only person suspended was the student who alerted his friend of the snap. The reason: “inciting conflict between two individuals.”

“The school never told [students] about the social media policy,” an unnamed student told the Youth Justice Board in a focus group. “The policy just pops up when the issue pops up.”

Eliminate or modify ‘gang database’

The bottom end of the “digital-savvy divide” is primarily made up of youth of color, a group the report said is disproportionately criminalized by NYPD’s gang database.

Police use wide-ranging criteria to identify potential gang members. Youth must exhibit two of the following “gang-related” traits: gang-related living location, clothing color, social association, documentation and scars, tattoos and hand signs. Another criterion is social media posts with gang members while wearing associated “gang paraphernalia.”

The report raised several questions about that. If someone shares a TikTok posted by a gang member, do they become a member by default? What counts as “gang paraphernalia” — could it be clothing or weapons? Researchers listed over a dozen colors associated with New York City gangs, claiming the criteria for the database was ambiguous.

“We had a difficult time identifying colors that were not gang-affiliated,” they wrote.

Youth listed in the gang database are at a higher risk of pretrial detention and often are often given longer sentences. In certain circumstances, the database makes it easier to prosecute youth on conspiracy charges, where federal judges can decide to charge minors as adults, the report said.

The first public discussion of the gang database came in June 2018 when Dermot F. Shea, then NYPD chief of detectives, testified before the New York City Council‘s Committee on Public Safety. Activists across the city have since urged NYPD to end the database, calling it racist.

The report made the same claim. Police monitor social media websites that are marketed toward Black people, the report said, citing WorldStarHipHop, Thehoodup and Imperialhiphop as examples. Websites frequently used by white supremacist groups — notably Reddit and 4chan — were absent from the list of websites police monitored, according to the report.

The Youth Justice Board recommended that the NYPD cancel the database and until then, heavily modify it. They also called on NYPD to stop sharing unsubstantiated information about minors with other agencies, such as the FBI and the U.S. Bureau of, Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives and to describe the database’s currently private demographic information.

Regulation and oversight

As the Youth Justice Board gathered data on youth social media usage and surveillance, they kept circling back to a question they could not answer. Who’s in charge?

First they looked at how city agencies operate their surveillance measures. Then they looked for data on how internet activities impact residents’ lives. They looked for who youth can report to if they feel their internet rights are violated.

What they found was a complex surveillance system with little public data or oversight.

With little comprehensive data on social media usage and almost no information for how it's monitored, they recommended several mandates to oversee how city agencies can use social media surveillance: the NYPD would have to disclose its surveillance methods, how it uses new surveillance technology and when social media is a factor in disciplinary measures. The report also calls on the city council to draft a Youth Bill of Rights with online protections for young people.

Much of this would consolidate protections for minors that they found scattered across different federal and state laws. All the recommendations would run through the city council.

Nearly two weeks after the report was released, Dee Mandiyan, program manager for the Youth Justice Board, said they haven’t heard from the city council, NYPD or the Department of Education.

“In the time since we interviewed NYPD and with city council folks a lot of things have shifted, so we’re not sure when they’re going to have the bandwidth to respond to what’s in the report,” they said. “But we’ll be looking forward to it when they do.”

This article has been updated.