We are now approaching the last quarter of 2013 and the subject of status offenders and what we should do with them or for them is still an active subject of discussion within the framework of our juvenile justice systems, and rightfully so. This is so despite the fact that our courts, law enforcement entities, child advocates, communities and law makers have been talking about this issue for more than 40 years. My bookshelves are lined with reports, studies, journals, task forces and more on the subject. Will we ever get it right?

We are now approaching the last quarter of 2013 and the subject of status offenders and what we should do with them or for them is still an active subject of discussion within the framework of our juvenile justice systems, and rightfully so. This is so despite the fact that our courts, law enforcement entities, child advocates, communities and law makers have been talking about this issue for more than 40 years. My bookshelves are lined with reports, studies, journals, task forces and more on the subject. Will we ever get it right?

Status offenses, as we know, commonly refer to conduct that would not be unlawful if committed by an adult but is unlawful only because of a child or youth’s legal status as a minor. Common status offenses include running away, incorrigibility, truancy, curfew violations, minors in possession of alcohol and tobacco and more. In Los Angeles, where I preside, we have had a court called the Informal Juvenile and Traffic Court (IJTC) for many of these offenses. In calendar year 2011, our IJTC handled approximately 65,000 citations including thousands for daytime loitering (aka truancy), curfew violations and possession offenses.

In 1974, Congress passed the Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act (JJDPA) that, among other things, limited the placement of status offenders in secure detention or correctional facilities because of concerns that the delinquency system was inappropriately treating these youth as criminal offenders. Partially due to concerns of judges, JJDPA was amended in 1980 to allow the detention of status offenders who had violated court orders such as “stop running away” or “go to school regularly.” That exception, known as the Valid Court Order exception (VCO), has resulted in the detention of thousands of youth classified as status offenders. The VCO is still in effect in most states, but there are significant efforts to eliminate it if and when Congress reauthorizes the JJDPA, which it has not done since 2002. There are good reasons for this, and there are positive developments in this area.

First, there is considerable research that has been done on adolescent brain development. We know that adolescents are different from adults. Adolescents are characterized by greater risk taking or sensation seeking and lesser ability to control impulses and resist pressure from peers and less likely to think ahead. We also know that as the brain develops and individuals mature into adulthood, these characteristics will decrease. Further, although holding youth accountable is important, it must be done in a way that does not harm them and endanger their normal development.

In accordance with the above, research shows that responses such as secure detention of status offenders is ineffective and potentially dangerous. Rather than punish them, youth, particularly status offenders, are better served by being diverted from the justice system. When you couple that with community programs that include engagement of youth and their families as well as programs designed to meet their specific needs, the chances of achieving positive outcomes for youth and their communities are greatly enhanced.

Judges can play a significant role in this process. In 2005, the National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges (NCJFCJ) published the “Juvenile Delinquency Guidelines” designed to “Improve Court Practice in Juvenile Delinquency Cases.” With respect to status offenses, the Guidelines recommend that juvenile court judges and others should work to divert status offenses to alternative systems whenever appropriate. There have been many examples where judges have endeavored to do just that.

A notable example is Judge Steven Teske from Clayton County, Ga. (Editor’s note: Judge Teske is a frequent JJIE contributor.) Using his judicial convening powers, Judge Teske brought together courts, educators, police, social services, parents, students, civic groups and churches. The result was the creation of a School Referral Reduction Protocol and the Clayton County Collaborative Child Study Team. The outcomes of these protocols have included fewer school referrals to court and higher graduation rates.

Judge David Stucki of Stark County, Ohio, who is the current President of NCJFCJ, helped create the Unruly Diversion Program, which was designed to hear complaints from parents about their child’s behavior and provide support before they could become formal charges of incorrigibility.

There are many more examples like these two judges and more resources available for courts, law enforcement, schools and communities to consider. The Vera Institute of Justice has created a Status Offense Reform Center to help policy makers create effective community based responses to keep status offenders out of the juvenile justice system and safely in their homes and communities. Resources include tool kits for status reform efforts, a library of information and more.

Last and certainly not least is the Coalition for Juvenile Justice Safety, Opportunity and Success Project known as the SOS Project. Products of SOS include its forthcoming National Standards for the Care of Youth charged with Status Offenses, perhaps the most comprehensive report on the subject to date; and a publication called “Positive Power: Exercising Judicial Leadership to Prevent Court Involvement and Incarceration of Non-Delinquent Youth.” This report contains numerous examples of positive and creative court leadership, including Judges Teske and Stucki, who have positively impacted their communities and systems.

These efforts and these resources are so timely and necessary today where the budgetary reality is such that courts do not have the resources, nor should they, to effectively deal with every issue that goes along with raising our children in our ever complicated world.

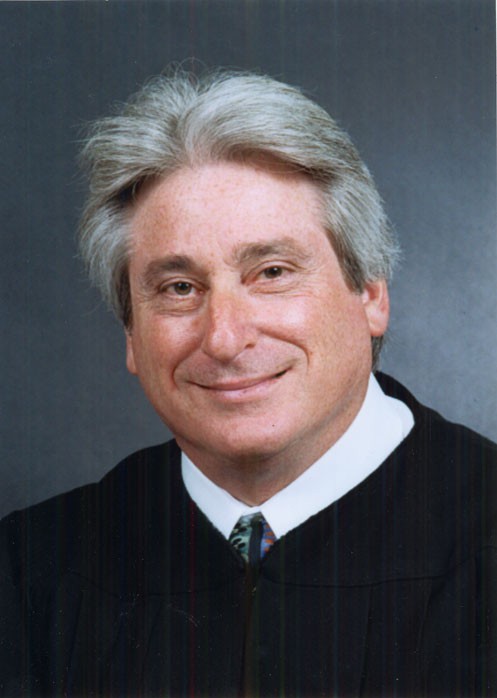

Judge Michael Nash was appointed to the Los Angeles Municipal Court in 1985. In 1989, he was elevated to the Los Angeles Superior Court and has served in the Juvenile Court since 1990. Since 1995, he has served as either Presiding Judge of the Juvenile Court or Supervising Judge of the Juvenile Dependency Court. Prior to being appointed to the bench, Judge Nash was a Deputy Attorney General in the California Attorney General’s Office from 1974-1985. Serving in the criminal division, he handled hundreds of cases in the Courts of Appeal including multiple appearances before the California Supreme Court. He was also co-prosecutor in the notorious Hillside Strangler trial from 1981-1983, the longest criminal trial in American history which resulted in conviction of the defendant.