Many states have not yet acted on advocates’ desire for quick release of all minors incarcerated for nonviolent, mostly misdemeanor offenses who are at risk of infection with COVID-19. There is pushback from opposing sides who feel releasing currently locked-up youth poses a safety risk.

National Juvenile Justice Network

Ricky Watson

Take North Carolina, where the population of incarcerated juveniles — about 400 youth — is down more than 20% in the last three weeks, according to Ricky Watson, executive director of the National Juvenile Justice Network, who is based in North Carolina.

But it’s not clear if these were releases of juveniles or just the result of a stoppage of court services statewide, he said.

“It’s been high stress, and there’s a lot of moving parts,” Watson said. “The advocates I’ve been working with are trying to make things happen here in North Carolina over the past week or two regarding COVID-19.”

What about staff?

No youth have tested positive so far in the facilities as of Sunday, William Lassiter, deputy secretary for juvenile justice under the state’s Department of Public Safety, told Watson.

“That’s good. But we don’t know” how often they’re being tested, if they’re asymptomatic, how many have access to testing and so on, Watson said, adding his group and others are pushing the state for more transparency on numbers, testing and the possible release of some youth.

“What are we doing for the people who are working shifts and coming in and out of the facilities?” he asked.

One nurse has been off work since testing positive in early March in Mecklenburg County, which covers Charlotte. The state Department of Public Safety (DPS) has suspended prison visitation with the exception of legal visits.

The state’s chief justice, Cheri Beasley, postponed court proceedings on Thursday through June 1. She also announced that payment of most fines and fees had been extended by 90 days. Clerks are instructed not to report late payments to the state.

Assuring that this move was not a statewide lockdown of prisons, DPS did not give a date when visitation would be reinstated due to the outbreak’s uncertainty. Instead, Beasley has ordered that officials throughout the state review all cases to determine juveniles and adults in correctional facilities who are eligible for immediate release.

Nationwide toll

By today, the United States had reported almost 357,000 coronavirus cases, and the American death toll from the global pandemic had passed 10,000, according to the tracking site worldometers.info.

Juvenile public defenders and advocates fear the worst for the estimated 43,000 minors in juvenile detention centers in the U.S. — and at least 4,000 youth in adult facilities — who are often without soap and other cleansers to regularly wash, as advised by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Sherika Shnider

“They eat their meals together, they shower together, they’re in the same sleeping areas,” said Sherika Shnider, a staff attorney with the National Juvenile Defender Center. “There’s no six-foot distance that can happen.”

These advocates and defenders are now in a collaborative push to release nonviolent offenders ahead of what the Trump administration has said could be the worst weeks of the coronavirus-related death and infection rates.

Those who have been sickened with COVID-19 have mostly been placed in solitary confinement, according to Shnider.

“Medical experts at the top of the field are saying that these detained and incarcerated populations are at such high risk of contracting COVID-19 that it's only a matter of time before this becomes a really large issue,” she said. “And they're seeing cases in facilities across the country. Youth are coming down with it; they have been positive. And in that situation, they just end up putting them in solitary confinement — which is already traumatic on top of the trauma that youth are experiencing being in a detention facility.”

Solitary generally entails confinement for 23½ hours a day. And there’s no guarantee that these cells housing sick youth have been sanitized, according to juvenile justice advocates trying to get these minors released.

“Imagine how scary isolating like that is,” Shnider said. “They're locking kids down, they don't have any care, any emotional support. It's just in many places what's happening to the people in these facilities. And you know, when you layer that with the fact that we know the majority of young people in this country are incarcerated for low-level, nonviolent actions, it's absolutely deplorable.”

Some places, like Colorado — which has released at least 22 juveniles and is evaluating 300 others — have started the process the advocates urge. Others, like Connecticut, Texas, New York and Illinois have started — or are reviewing — releasing nonviolent juveniles to be cared for at home or in other safe places.

"It really varies state to state, right?” Shnider said. “We are very, very lucky to have really active defenders across the country. So, you have like Prince George's County in Maryland, and Cook County in Illinois — they're all reviewing use cases for relief. Cook County, about a week and a half ago, started really actively reviewing cases. And courts are starting to close.”

Shuttering courts, of course, will cause an immense backlog of cases when they do reopen.

“But we do feel really lucky that we’re seeing states that are trying very hard to do early release and reviewing cases,” she added. “Just because we recognize that that's one of the only avenues that we have where we're really going to be able to stop the spread by stopping putting youth in in the first place. And so now we need to really work on getting kids out.”

Unequal chances for youth

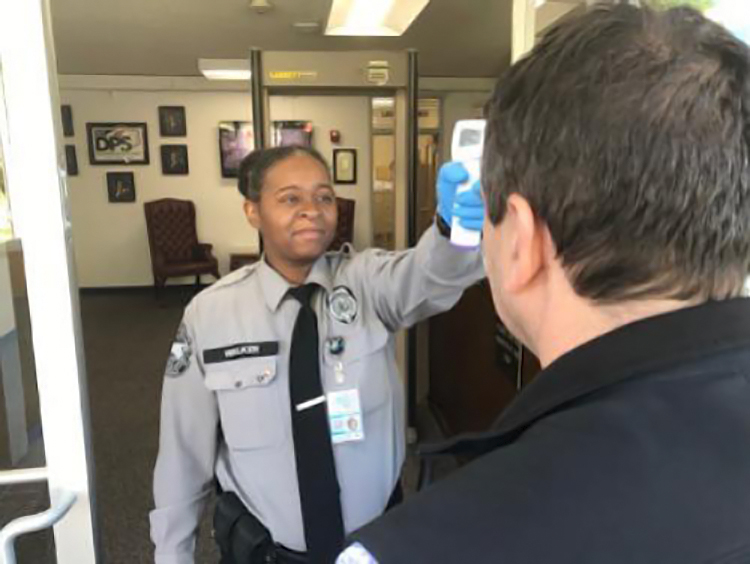

The playing field is not fair, according to those pressing for change, with detention staff properly equipped while youth are not.

“It’s a huge struggle that our defenders are running into,” Shnider said. “Yes, correctional officers are being protected, and given gloves and maintaining distance from us [and youth]. But do youth have that luxury?”

The simple answer is — short of solitary — no.

In North Carolina, new admissions to the juvenile justice system will be placed in medical confinement for one week until a medical provider clears them to join the rest of the population.

All juveniles will also be screened before transportation, and any youth showing respiratory illness will not be transported at all.

Additionally, many of the usual services are going digital, with phone calls temporarily replacing visitation, essential court hearings being conducted via video and medical services provided with telehealth.

But this is not an equal chance to stay in touch with people who care for these youth, as correctional phone calls cost money — often leaving out indigent youth who are incarcerated.

And even with these measures, juvenile advocates say it’s not enough. Much like an adult jail or prison, juvenile facilities have cells that are squeezed together.

North Carolina Juvenile Defender Eric Zogry also raised an issue that could complicate releasing some juveniles:

“As soon as this [pandemic] started, this was the main issue — how to remove people from confinement so they’re not locked in and subjected to this,” he said. “In the juvenile world, you can’t just necessarily open the gates and release kids, right? Because they can’t drive, or they may not have a home to go to. So, it’s a little more complicated on this side. And I will say that, there’s a lot of complexity with this. We’ve got 100 counties in North Carolina, and every court does things just a little bit differently.”

Some courts have shuttered until further notice while others are operating on staggered calendars or meeting rarely, such as once a week in the larger counties, Zogry said.

“I would feel better if we knew more information about what other efforts the state is taking to rapidly reduce the population,” Watson said. “I think there have been some good steps, but again, I think with a little bit more transparency, I would feel a lot better.”

This story has been updated.