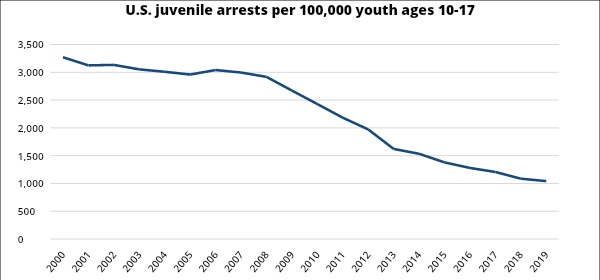

![]() Youth arrest rates have plummeted over the past several decades, falling nearly 70% nationwide since 2000, including a 54% reduction in violent offense arrests. There are now fewer youth in juvenile halls or courtrooms and far smaller probation caseloads. Yet state and local governments continue to invest heavily in juvenile justice, shoring up systems that are known to cause harm.

Youth arrest rates have plummeted over the past several decades, falling nearly 70% nationwide since 2000, including a 54% reduction in violent offense arrests. There are now fewer youth in juvenile halls or courtrooms and far smaller probation caseloads. Yet state and local governments continue to invest heavily in juvenile justice, shoring up systems that are known to cause harm.

Sources: Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (2000-19); Annie E. Casey Foundation, Kids Count Data Center (2000-19)

Amid the current economic crisis, maintaining overbuilt juvenile facilities and bloated probation budgets squanders resources that schools, health systems and community-based service providers desperately need. Moreover, funding excessive facility space can needlessly sweep youth into a system bent on self-preservation.

In California, like much of the country, juvenile justice systems have experienced significant population reductions. With fewer youth being arrested, detained, prosecuted and confined, juvenile facilities are operating far below capacity. California’s state-run Division of Juvenile Justice (DJJ) facilities are 43% full and the state’s 109 juvenile halls, camps and ranches are averaging 19% occupancy. These trends, which have driven per capita costs up to $300,000 at DJJ and over $500,000 in some local facilities, pose a threat to the survival of juvenile facilities and broader juvenile justice systems. For example, some California counties are considering closing their juvenile halls, several communities are fighting to wrest back funding and programs from their highly punitive probation departments and the state recently moved to shut down its barbaric DJJ facilities.

Over the past few years, correctional leaders and their lobbyists in Sacramento have pushed for grants and law changes that would help sustain their systems in the face of shrinking responsibilities. In response to a 2007 reform narrowing the criteria for sending youth to DJJ, the state allocated $300 million to build new county juvenile facilities. This investment in correctional infrastructure occurred amid clear declines in justice-involved youth populations.

Maureen Washburn

One county, Monterey, has twice reduced the size of its planned juvenile hall in response to community pressure and budget overruns. It originally received state funds to support a 150-bed facility, but now plans to construct 80 beds — Monterey’s current juvenile hall has a population of just 33 youth, while its Youth Center, which houses youth long term, has a population of 21. Few other counties have made such adjustments to their juvenile hall projects, deepening the state’s long-term investment in locked facilities.

In another move to bolster county lockups, the California Legislature passed a series of bills, beginning in 2016, that opened up some county juvenile halls to young adults. Though the legislation was touted as creating a humane alternative to jail, its champion was the Chief Probation Officers of California (CPOC), a group representing those who run juvenile halls. It was a transparent effort to boost facility populations and ensure continued funding for probation.

Similarly, in 2018, the state approved a plan for DJJ facilities to increase their age limits and pilot a program for young adults whose offenses occurred after age 18. The proposal coincided with an all-time low in DJJ’s youth numbers. Since then, its population increased from just over 600 youth to nearly 800.

Despite these attempts to prop up the state system, in 2020 California leaders took the historic step of ordering DJJ’s closure. The closure process, which will take approximately two years, will put an end to DJJ’s 80-year history of violence and abuse. It is an important acknowledgment of the harm done to tens of thousands of youth at the hands of the state. Yet it was likely the system’s relatively low population during an economic downturn that made closure politically viable.

Some counties may become regional hubs

Now, as state leaders develop a plan for phasing out DJJ, they are looking to redirect substantial funding into shrinking county correctional systems. Following months of lobbying by CPOC and others, the state is now poised to allocate up to $213 million annually to counties — roughly the amount currently budgeted for DJJ — plus $10 million in one-time funds, which are likely to be spent on detention facilities, and $50 million for implementing this reform and one other.

California counties already receive roughly $300 million each year through two state grant programs, the Youthful Offender Block Grant and the Juvenile Justice Crime Prevention Act. Due to a combination of lax oversight and probation supremacy, counties funnel most of these grant dollars directly into probation budgets to fund juvenile facility operations and programs that sweep more youth into the justice system. (CJCJ is sponsoring a state bill this year to redirect funds into communities.) Amid marked declines in the state’s justice-involved youth population, these state grants have only increased in size, augmenting an overbuilt system.

For more information on juvenile justice issues and reform trends, go to JJIE Resource Hub

DJJ’s closure will create an opportunity for some counties to serve as regional hubs for youth who would have been sent to the state system. Thus far, 12 counties have expressed interest in accepting youth from other counties. If selected, counties will receive a share of the state’s $10 million grant for the establishment of these multicounty models. More significantly, they will collect regular reimbursements from partner counties. This influx of funding and youth could sustain some county systems for years to come. Included in the list of potential hubs are San Mateo and El Dorado — counties whose boards of supervisors have considered closing or have moved to close their juvenile halls due to population declines.

In recent years, California has embraced groundbreaking juvenile justice reform. Yet many decisionmakers do not acknowledge the massive declines in youth arrests that have made this progress possible. The result has been continued exorbitant spending on systems that harm.

States across the country must heed California’s example and prioritize divestment as part of their justice reform efforts. Pulling money out of probation and correctional systems can shrink them for good and end their pursuit of new populations to detain, monitor and confine. These punitive systems do not advance justice, accountability or healing. Young people deserve reinvestment in the community-led programs that keep them safe and healthy.

Maureen Washburn is a member of the policy and communications team at the Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice.