Charles Kennebrew tours the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C. Videographer: Micah Danney

Three months after the gang he’d been devoted to lured Charles Kennebrew to a supposed meeting about gang business, then jumped and brutally beat him, the 37-year-old stood staring at a slave auction block in Washington, D.C.

Farther along, the now former gangster and others in their group of formerly incarcerated men navigated the National Museum of African American History and Culture exhibits on Black soldiers who fought in the Civil War and on civil rights heroes.

“You see?” began the former prosecutor, who’d organized that day trip down from New York for those 20- and 30-something former incarcerees she mentors. “Think about the history you were taught versus this history. Imagine if you had been taught this history. Think about that. Where would those boys be?”

Kennebrew pondered that as he listened to the near-whispered lessons coming from Risco Mention-Lewis, acting commissioner of the 2,349-officer Suffolk County Police Department on Long Island.

Kennebrew has known her since he was a teenager, rebuffing her interventions as she tried to help him straighten out. That day, taking in what surrounded him inside that museum, he considered his own story. It’s a cautionary tale about the costs and benefits of leaving gang life and trying to figure out, Kennebrew said, where he might have wound up had he better known himself and the lessons that museum tells.

“I just thought: Just slaves … They just caught us,” Kennebrew said during the train ride home. “I didn’t know, before, the position we were in and the way we carried ourselves. Maybe if I had known that, I probably would have been moving differently — from the jump.”

He meant that he might have pointed himself in a different direction early in life had he been more steeped in that history.

Micah Danney

Charles Kennebrew, 37, left the Bloods last year after more than two decades in the gang.

There is no recent official count of how many individuals, like Kennebrew, have departed gang life. In 2012, the most recent year that the U.S. Department of Justice National Gang Center estimated the data, roughly 850,000 members were in some 30,700 youth gangs across the country. More than half of those youths — 57% — were in large cities. Suburban counties were home to about 25% and smaller cities contained 16%. Those numbers decreased from 1996 through 2002, then increased steadily over the next decade.

A 2014 study in the Journal of Quantitative Criminology found that 70% of gang members joined as adolescents and left before adulthood.

“Typically, the research finds that they're only in there about a year or two and then they age out for many different reasons,” said Meena Harris, the gang research center’s director.

Said David C. Pyrooz, a University of Colorado Institute of Behavioral Science gang researcher: “Gang membership is a trajectory in the life course. It’s a pathway of development not unlike other predominant trajectories that bring meaning to our lives."

Key to that trajectory is what researchers call embeddedness, the degree to which a member’s life is enmeshed with the gang. Indicators of embeddedness include how high-profile or respected one is in that world; the number of close friends who also are in the gang; and the frequency and degree of displays of gang membership, including hostility toward and influence over others.

As a teen, Kennebrew rated high in every category. His devotion deepened as he passed into adulthood, said Kennebrew and others who knew him over that time. His identity was tied up in being a standard-bearer for the Bloods — so much so that, even after being jumped and beaten, he has struggled to disentangle his self-worth from his angst over being disapproved of by the people who’d brutalized him.

“It hurts,” he said. “But, at the same time, if I ain’t gonna be a part of that no more, I shouldn’t care about what people have to say.”

Crossroads and wrong turns

When she was a prosecutor in neighboring Nassau County, Kennebrew’s home turf, Mention-Lewis expressly asked to be assigned cases of teenagers who were in gangs.

Kennebrew, she said, “was an up-and-coming problem for the community. So, what I did was I tried to get next to those guys.”

She used a variety of tactics. To determine how committed to the gang they were, she would ask them to write essays. She’d get her answer when Bloods would cross out the c’s in their essays and Crips would cross out the b’s. Her approach included enrolling some who may not have been drug-addicted into drug treatment programs because, she said, they “needed a time-out.”

Kennebrew wasn’t a drug addict and he wasn’t willing to be treated like one. Even though some of his decisions were doing him a real disservice, Mention-Lewis appreciated his resolve. Helping the Kennebrews of the world sharpen their decision-making skills and see more options for themselves is at the core of the community work she does.

At 16, Kennebrew was especially smart, she said.

“She saw something different in me that she didn’t see in other people,” Kennebrew said, chuckling. “She always used to tell me, ‘Yo, you’re a professor.’”

He was calm, bespectacled and serious, especially about his loyalty to the gang, Mention-Lewis said, reflecting on teenaged Kennebrew.

“I could have easily seen him … at Harvard,” she said. “It’s fascinating that he became, basically, the professor for the gang. He was very dedicated to the rules, very dedicated to the history. I told him, ‘ ... The gift God gave you for teaching, you used it for evil.’”

She’s seen a common theme over the decades: Boys and young men who are drawn to gangs don’t have a sense of the good they can do in the world. And they don’t believe they have much prospect of succeeding, based on conventional measures of American success, outside of that gang realm.

What feeds that pessimism is that many of them don’t have a grasp of what people who look like them have achieved, which, in part, is a failure of systems, including public schools, Mention-Lewis said. When her own daughters’ Long Island middle school history books called slaveowners “planters” and claimed that their wives shouldered responsibility for dressing and providing for the people they enslaved, she created a curriculum to counter. As a school volunteer, she taught that curriculum, placing Black abolitionists who were absent from those textbooks against white abolitionist John Brown, who was in them.

“The whole point of the African American Museum trip,” she said, pointing to Kennebrew, “was to show him who he should have been, why his ancestors died for him to be better than he is, better than the journey he took.”

Forging gang kinships as teens

Included among the museum day-trippers was Ducamel Denis, now 35, who Mention-Lewis also met when he was an adolescent. Kennebrew and Denis had connected in their early teens during Kennebrew’s frequent visits with a close friend who was one of Denis’ neighbors in New Castle, a small hamlet that’s a 20-minute commuter train ride from the easternmost edges of New York City. Denis looked up to Kennebrew, whose spanking clean, signature Chuck Taylor sneakers and crisp jeans Denis still remembers.

The older boy looked out for Denis and his friends, walking them home from Westbury Middle School to protect them from MS-13, a notoriously ruthless Salvadoran gang that was trying to assault younger Black boys. It was retaliation, Kennebrew said, after a previous generation of Black street gangsters had similarly targeted Hispanic kids.

Denis and his friends followed Kennebrew into gang-banging. And Kennebrew taught them the gang’s rules; how to position the red laces on their sneakers; and to always hang their red bandanas from their right pants pockets (Crips pocketed their blue bandanas on the left). For those younger kids, Kennebrew charted founder Omar “O.G. Mack” Portee’s launch of the East Coast’s United Blood Nation. Bloods who knew those details tended to advance through the ranks quicker than gang members who were unaware.

“You had to know your history about the set that you was claiming. If you didn’t, you would be G-checked,” Denis said, referring to senior Bloods’ random interrogations of anyone wearing their colors. There were potentially violent consequences for anyone who gave a wrong answer.

“So,” Denis continued, “we would basically run up on one another and find out, like, ‘What’s your handle, what’s your name? What set you’re claiming, what’s your status in that set, who were you under?’ And Charles was one of the people that always wanted to make sure that nothing would happen to us if that was to ever be a situation.”

As the boys burrowed into that lifestyle, networking and building their reputations among gang sets in New York City’s five boroughs, Mention-Lewis said she kept seeking them out, trying to persuade them to choose a different path.

Those she could locate, she had more success in steering in more positive directions.

“Charles,” she said, of Kennebrew, “was hard to find.”

Denis, though, chose to leave the gang when he was 19, after surviving a gunshot in the back. He entered a drug treatment program. And Mention-Lewis took him under her wing, having him speak to students at nearby Hofstra University and to teenagers at trade and other alternative schools for those who’d been kicked out of regular schools for misbehaving. Those experiences, she said, helped show Denis how sharing his story could help people.

But Kennebrew rejected Mention-Lewis’ entreaties. He ramped up his gangsterism. He volunteered for violent confrontations with rival gangs. He went to prison the first time, in 2008, on a federal gun-possession conviction that had him locked up for three years. A conviction for second-degree attempted criminal possession of a weapon got him sentenced to two and a half years, his last bid in prison. He was paroled in June 2020, returning to a world in quarantine and erupting into street protests against anti-Black racism. He laid low for the next 12 months.

Rising through leadership ranks

Kennebrew was in eighth grade when he and about a dozen friends formed that street gang to counter MS-13’s presence in their neighborhood and in front of that middle school. The Bloods’ elders did require younger members to attend school, even checking their report cards, he said.

The gang’s own curriculum included books about Black history, militancy and Black nationalist leaders such as Marcus Garvey, Kennebrew said. He embraced the educational component as a path to gang leadership as the Bloods were expanding their presence throughout New York’s prison system by recruiting young men while they were incarcerated.

Courtesy of Charles Kennebrew

Charles Kennebrew (center), while in federal prison with fellow members of the Bloods.

Over more than a decade of being incarcerated, Kennebrew continued to teach, including helping other men learn to read, hoping that would persuade them to avoid performing gang activity at other members’ behest that might worsen their situation behind bars. Upon release from prison, those men were expected to remain part of a brotherhood, sending care packages and money to those still in prison and helping them stay in touch with their families.

Kennebrew lived through wars with rival gangs like the Latin Kings until the Bloods were the dominant gang throughout New York’s state prisons. At that point, rivalries turned inward, Kennebrew said, Blood against Blood. His status and sacrifices for the gang made him unwilling to back down when his stance on something was challenged, which had him butting heads with other leaders.

That allegiance merited something much more than last year’s beat-down by men he tried to honor, he said. More than the pain of being bruised, covered in abrasions and gashes and unable to see out of his right eye, his more profound hurt stemmed from being betrayed, degraded. “I felt embarrassed,” Kennebrew said.

The attack, Kennebrew believes, resulted from younger, envious Bloods spreading lies about him. He was unaware of the falsehoods. But he suspected someone high up the ladder signed off on the attack or chose not to warn him.

Resetting a personal compass

“Charles confused gang-hood with manhood,” mentor Mention-Lewis said. “A lot of guys confuse gang-hood with manhood … But they never had any good men around them so they don’t know what manhood looks like.”

Unlearning the behaviors that got formerly incarcerated people into trouble is the aim of the Council of Thought and Action, which Mention-Lewis founded in 2008. “Crazy-house rules” is what she calls the self-destructive beliefs and habits of many who are born and reared in heavily dysfunctional families and communities. Dysfunction, she said, is the only norm that many of them know.

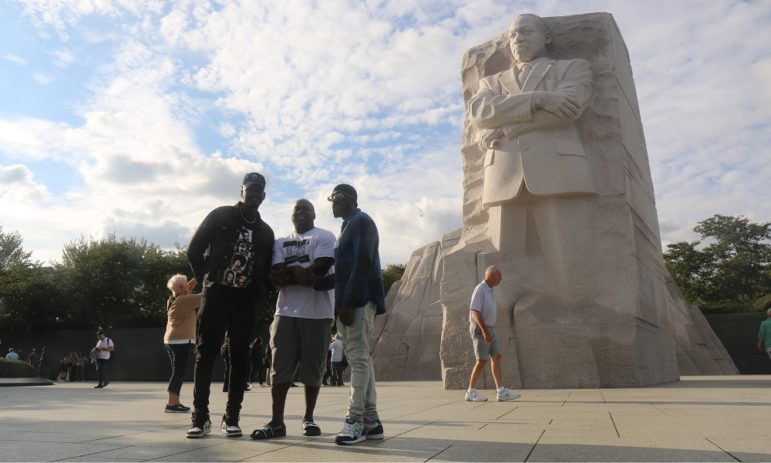

Micah Danney

From left, Ducamel Denis, Calvin Harris and Kennebrew at the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial in Washington, D.C.

“For a time in their lives, they’re just lost value,” Mention-Lewis said. “They’re valuable, and we need to find ways to give them the tools and information they need to stay connected to this world.”

Though life after the gang bores him, Kennebrew said, he’s progressing. He avoids the corner stores where his old contacts hang out, going elsewhere for cigarettes or food. Downloading a few streaming services onto his phone keeps him from going to anyone else’s place to watch movies. Mostly, he stays inside at home with his mother, making music, writing about his past and trying to keep busy. Attending a substance abuse program satisfies his parole officer. And although he says he doesn’t have a drug problem, the group therapy has been helpful.

He works full-time at a meat-packing warehouse. He’s focused on getting his own apartment and a car before determining his next steps, which he hopes will lead to something closer to a full-fledged career, not just a job. He’s been getting closer to his girlfriend and their two daughters, 17 and 19. As he steps up his parenting, he’s talking to his girls about boys, about how to conduct themselves as they enter young adulthood.

Seven months into a new existence, Kennebrew feels lighter, less burdened by what it took to uphold his status. His progress is slow, he said, but steady.

“My life is an example for these kids not to join gangs,” he said, “because, if you do, this is what you’re going to go through.”

Micah Danney has covered human rights, criminal justice and other issues for The Crime Report, New York Daily News, Newsweek and others. He spent 14 months in a New York prison for drug-dealing.