Photos by Gwen McClure

Te Wharenui (the carved meeting house) of Manurewa marae.

AUCKLAND, New Zealand — It’s midmorning on a Friday in Manukau’s Youth Court, and Judge Philip Recordon is sitting behind the bench, speaking to Thomas, a young teenage boy (his name has been changed to protect his privacy). The others in the room, including police prosecutor Sgt. Richard Spendelow, a lawyer, and representatives from Child, Youth and Family (CYF), are discussing Thomas’ case while he stands quietly.

Recordon tells Thomas he can sit down, then sets his curfew: He isn’t allowed out between the hours of 7 p.m. and 7 a.m. unless he’s with his mother or aunt, and he’s not allowed any contact with the friends he was with when he got into trouble. Thomas’ mother sits behind him, her forehead furrowed. They’ve recently lost their house, and though they have short-term, emergency housing, the stress of that situation is clearly compounded by her son’s court case.

Spendelow looks at her and asks that if her son breaches curfew, she call the police. She nods.

Spendelow turns back toward Thomas.

“You can tell the judge whether your mom’s going to have to make the call that will break her heart,” he says.

For more information, visit the JJIE Resource Hub | Community-Based Alternatives

Thomas’ charges are for trespassing, burglary and using threatening language. That they landed him in court mean they’re considered serious — experts estimate that only 15 to 20 percent of youth offenders end up in court. For the remainder of the cases, which are often petty, opportunistic crime, police have the flexibility to make decisions based on the context and details of the case, with a focus both on diverting young people from entering the court system and involving their families and communities in the rehabilitative process.

“You often get a young person where things go wrong; there might be divorce at home or someone dies or there’s some kind of crisis and they might commit a lot of minor persistent offending over a couple of weeks or a couple of months,” said Nessa Lynch, senior lecturer at Victoria University School of Law. “The New Zealand system allows police officers to really use their discretion and their common sense to deal with that situation.”

Nearly two months later, Thomas has transitioned to Te Kooti Rangatahi (youth court, in Māori). Though in many ways the court setup is similar — the same laws apply, and lawyers, lay advocates, a police prosecutor and social workers operate under a presiding judge — Te Kooti Rangatahi is specifically for Māori, a group that makes up 62 percent of young offenders who appear in court, and approximately 16 percent of the overall population.

Held on the marae, which is a Māori community space, the Rangatahi court incorporates tikanga Māori (roughly, Māori culture) into the court process. Since 2008, when the first Rangatahi court opened in Gisborne, New Zealand, 13 more have opened around the country. There are also two Pasifika courts in Auckland, focused on incorporating cultural practices from various Pacific Islands.

In addition to the cultural aspects (including a pōwhiri, or welcoming ceremony, to begin the day), the main difference is the involvement of Māori elders, who sit on a couch along the wall and take turns speaking after the judge.

In court, Thomas introduces his mother to Judge Gregory Hikaka, the presiding judge, as he did in Judge Recordon’s court. This time though, he introduces himself with his pepeha, a recitation of his ancestry. The introduction serves to tell the court who he is and where he comes from, with the goal of rooting him further into his culture.

“Hopefully it’s a way to make them proud of who they are,” said Judge Frances Eivers, who also presides over Rangatahi courts.

In 1985, then-Minister of Social Welfare Ann Hercus commissioned a report on her ministry, asking a committee to examine how well it worked with Māori. The result was a damning report called Pauo-te-Ata-tu (Daybreak) that focused on institutionalized racism targeting Māori.

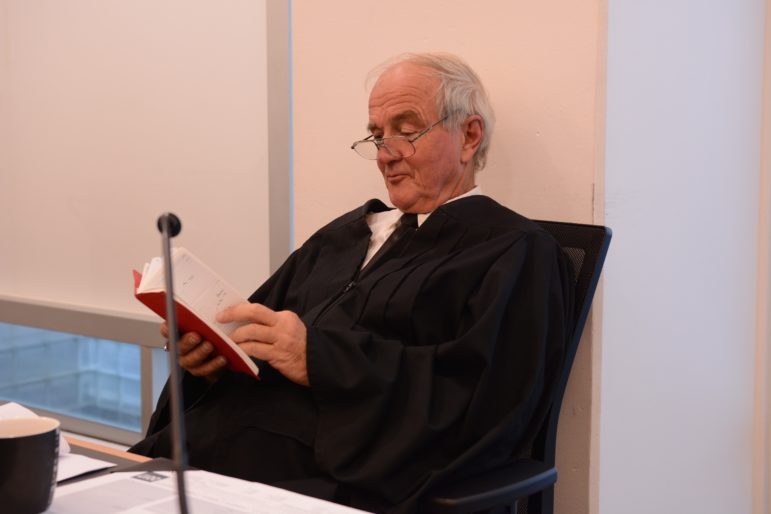

Judge Philip Recordon behind the bench in Youth Court.

Partially in response, in 1989, the Children Young People and Their Families Act overhauled the processes in place, which largely still looked at the justice system as a way to care for children in need. The new act emphasized the importance of family and culture in the youth justice system, and shifted the focus toward diverting offenders from formally entering the system.

While CYF (which is currently transitioning to the title “Ministry for Vulnerable Children”) and the Ministry of Justice partner in administering youth justice, the police department is perhaps the biggest player in the system, as the first and often last line of defense. They are required to handle as many cases as possible outside of the courts.

Ross Lienert, youth manager for the New Zealand Police, says the majority of young offenders are “adolescent limited,” meaning that their offending is limited to their teen years, and they won’t continue to commit crimes past adolescence.

“They would stop offending if we did nothing at all, so the response is generally pretty light — reparation, an apology, some form of closure,” he said.

In addition to punitive measures, part of the police’s work is to remove the need to commit these offenses again. A teen who has committed a minor assault may be required to attend anger management classes; one who is driving without a license may be supported to get his or her license. Depending on whether or not victims are involved, this may be enough. Otherwise, the case is escalated.

“Legally we’re required to deal with the underlying causes, but we also need to hold the child or young person accountable for their offending and deal with the victims,” Lienert said.

One of the tactics that goes hand-in-hand with court is the Family Group Conference (FGC). When a case is too serious to be dealt with by the police alone, it will be sent to an FGC. FGCs are the core of the youth justice system, and nearly all offenders who commit a serious offense will be required to attend one. If a child is arrested, they will first go to court, then an FGC.

In the conference, a facilitator, offenders, their families and other professionals meet to discuss a plan. The first step is to discuss the offense and for the young person to admit their wrongdoing. Next, everyone except for the family leaves the room, and the family and offender develop a plan to hold him or her accountable. This could include community service, drug and alcohol counseling or even parenting programs for the offender’s family. In the final step, everyone meets again to discuss the plan and assign roles and responsibilities to everyone in the room.

In FGCs, the victim is entitled to be there. Although not all conferences involve the victim, the ones that do fall under the restorative justice category. While definitions of restorative justice vary, the main theme is the idea that providing a healing process for the victim and the offender allows the offender a better chance of rehabilitation, and the victim a greater sense of justice.

“The theoretical idea is that you’re supposed to be be returning the power of the offense to the people who are most affected by it,” Lynch said.

Paul Hapeta, a Family Group Conference facilitator who works in Wellington, has seen lots of success come from the FGCs. One that stands out for him is a conference where a young boy had done a “smash and grab” from a local shop, stealing valuable merchandise. As part of FGC plans, many young offenders are required to do community work. Instead, he was sentenced to work in the victim’s shop after school for three months, learning valuable skills in addition to working toward reparations. After he completed the service, the shop owner offered him a job.

Police Prosecutor Sgt. David Mundy, Māori elders Toimai Katipa, Mere Komene (back), Judge Gregory Hikaka, elders Te Miharo Munro and Taipari Keepa inside Te Wharenui (the carved meeting house).

“The victim feels satisfied that he’s part of the solution and the young person gets to experience something they otherwise would not have experienced, and they don’t see the victim as being a faceless person any more,” Hapeta said.

For cases more serious, like Thomas’, offenders will end up back in court after the FGC, but that doesn’t mean the charge will always stay on their record. Depending on the charge’s severity, and whether the teen meets the requirements, the judge can decide to give a “282 discharge,” which in effect clears their record, meaning that they go into adult life without a criminal history. For Thomas, this can mean the ability to travel out of the country in a few years to pursue his dreams.

As she does every time an offender receives a 282 discharge, Te Miharo Munro, one of the four elders, stands up to sing a song of appreciation and respect to Thomas.

Te aroha (Love)

Te whakapono (Faith)

Me te rangimarie (Peace)

Tatou tatou e (For us all)

“You’ve grown in stature. Do you know what that means?” Judge Hikaka asks, and for the first time, Thomas smiles.

“It means you’ve grown to be a more responsible young man.”