Story by John Kelly and Ryan Schill

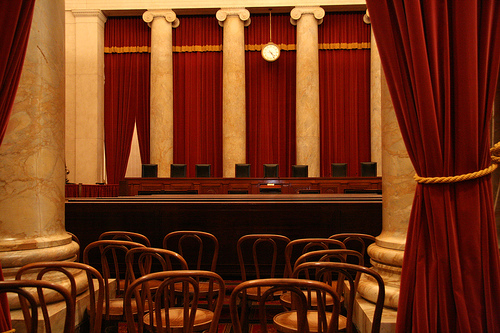

Today, the Supreme Court will hear oral arguments in two murder cases that resulted in mandatory life without parole (LWOP) sentences for juvenile offenders, both of whom were 14 at the time of crime. At the heart of both cases is the question of the constitutionality of sentencing a minor to die in prison.

Below is a primer with everything you need to know about Tuesday’s oral arguments, and what events led up to them.

The issue

Life without the possibility of parole, which has the common shorthand of LWOP, is the most severe penalty other than death that is handed down to convicts. A prisoner who receives an LWOP sentence will never have the opportunity to become a free citizen again, regardless of his or her attempts to rehabilitate in prison.

More stories:

OP-ED: The High Court Should Hold to Constitutional Principle and End Juvenile Life Without Parole

There are 49 states that allow prisoners to serve life sentences without a chance at parole; only Alaska mandates some opportunity for release. In some of those states, such as Florida, a life sentence has become an inherent LWOP sentence because the state has no parole system in place.

Aside from Alaska, according to The Campaign for the Fair Sentencing of Youth, there are six other states that already prohibit LWOP sentences for juvenile offenders: Colorado, Kansas, Kentucky, Montana, New Mexico, and Oregon. Another five - Maine, New Jersey, New York, Vermont, and West Virginia – do not currently have any offender serving an LWOP sentence for a crime committed as a juvenile.

The federal government also permits juveniles to receive LWOP sentences, according to the Campaign, and there are approximately 36 federal inmates who have received LWOP for crimes they committed before the age of 18.

Cases currently before the Court

Kuntrell Jackson

The Court will first hear arguments in Jackson v. Hobbs, in which the offender, Kuntrell Jackson, did not commit the homicide for which he received a life sentence without parole. Jackson and two older boys quickly schemed a plan to rob a video store while walking together through their neighborhood on Nov. 18, 1999, just 17 days past Jackson’s 14th birthday. He was unaware one of his friends was hiding a shotgun in his coat until just before the robbery.

Jackson remained outside while the other two boys entered the store, not following inside until just before one of his friends

shot the clerk, who had refused to give them money. The three immediately fled without taking anything from the store.

Jackson was eventually convicted of capital murder for his involvement in the homicide, a crime that, under Arkansas law where the murder occurred, carries a mandatory life sentence without parole regardless of any mitigating factors.

Miller v. Alabama will be argued in tandem with Jackson v. Hobbs and involves Evan Miller who, in 2003 at age 14, robbed and beat an older neighbor with a friend. The two boys drank and smoked pot with Miller’s neighbor in his trailer until he passed out, at which point they stole money from his wallet. But while they tried to slide the neighbor’s wallet back into his pants, the neighbor jumped up and grabbed Miller by the throat. Miller’s friend then hit the neighbor in the head with a baseball ball freeing Miller who began to punch the neighbor repeatedly in the face before grabbing the bat himself and continuing the attack.

Evan Miller

The pair left but returned soon after to clean up the blood. As they departed a second time they set the trailer on fire to hide the crime. The neighbor, unable to move after the attack, died in the fire. Miller was convicted of murder and received a mandatory life sentence without parole.

What came before

Two previous rulings by the Supreme Court laid the groundwork for Tuesday’s oral arguments. The high court abolished the death penalty for minors in 2005, and in 2010 eliminated LWOP sentences for juveniles convicted of non-homicides.

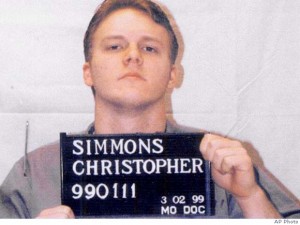

In the 2005 case, Simmons v. Roper, Christopher Simmons was sentenced to death for a murder committed in 1993, when he was 17. The jury found Simmons guilty of breaking into a Missouri woman’s home, binding her feet and hands with duct tape and then throwing her off a bridge, drowning her in the river below.

In a 2005 ruling on the case, the Supreme Court deemed capital punishment to be unconstitutional for anyone under the age of 18, citing the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition against cruel and unusual punishments and the “evolving standards of decency what mark the progress of a maturing society.” Writing for the majority, Justice Anthony Kennedy pointed to the “comparative immaturity and irresponsibility of juveniles.”

In 2010, the Supreme Court took another step in Graham v. Florida, using the case to strike down life sentences without the possibility of parole for all non-homicide crimes committed by juveniles. The case involved Terence Graham, who was arrested for a 2003 home invasion robbery when he was 16. The offense was a violation of the terms of his probation from a plea agreement in an earlier armed robbery conviction. A Florida judge sentenced Graham to life, a sentence that inherently carries no opportunity for parole in the state, which abolished parole in 1983.

Christopher Simmons

The high court found life sentences without parole for juveniles convicted of non-homicide crimes to be unconstitutional, deeming it in violation of the cruel and unusual clause of the Eighth Amendment. Justice Kennedy, again writing for the majority, said the State must provide the offender with “some realistic opportunity to obtain release” before the end of their sentence but is not bound to guarantee the offender’s release.

What might happen: The court’s attention to the Roper case followed its longstanding mantra that “death is different.” Graham effectively took the court’s actions on juvenile sentencing to a new realm: that youths are different. Now, the high court must go back to contemplating whether death is different, but this time it will be the death of a homicide victim, not a convict.

It is entirely possible that the train stops here, and the court decides not to infringe upon the ability of states to impose LWOP on juveniles that are convicted of homicides. Should the court choose to limit juvenile LWOP sentences in homicide cases, it could do so in several ways:

-A complete ban on LWOP for juveniles. This would require that all states develop some sort of parole system for all juvenile offenders convicted of life sentences.

-A ban on LWOP for juveniles below the age of 15. There are only 73 current LWOP inmates who were convicted for crimes they committed when they were 14, and nine others who were convicted when they were younger.

Justices have explored the idea of bright-line rulings that would distinguish younger juveniles from older ones in two recent cases – Graham and JDB v. North Carolina, which dealt with police questioning – but decided against it in both cases.

-Judicial review of juvenile LWOP usage in mandatory sentencing schemes. In both cases, the court’s list of “questions presented” includes references to the constitutionality of sentencing juveniles to LWOP under mandatory sentencing schemes that categorically preclude consideration of the offender’s age.

Such a ruling would seem to fall in line with Chief Justice John Roberts’ suggestion during the Graham oral arguments that requiring review of LWOP in all juvenile cases would be more practical than a categorical ban on the sentence for certain offenses.

One concern the justices may harbor in regard to this result would be setting the precedent of subjecting mandatory sentencing to mitigating factors. A mandate that judges consider age as a factor opens up mandatory sentencing schemes to similar challenges for parties claiming exception.

-A ban on LWOP for juveniles who did not commit the act that resulted in homicide. Some of the inmates doing LWOP sentences for juvenile offenses, including Jackson, were convicted of homicide because they were present for the action that precipitated a homicide.

This is the key difference between the two cases taken up by the court today. Both cases question the constitutionality of LWOP for young teens, specifically those subjected to mandatory sentencing schemes, but only Jackson’s case presents a separate question about the fairness of LWOP for a juvenile involved indirectly with a homicide.

Who we're talking about: There are approximately 2,570 offenders serving LWOP for offenses they committed as a minor. There appears to be no good estimate on how many of those offenders are in for homicides they caused directly and how many are offenders who were present for a crime that included another offender killing someone.

Where this matters most: As mentioned, all but seven states allow for juveniles to die in prison. But judges in five states take advantage of the LWOP option for juveniles far more often than colleagues in other states. Nearly two-thirds of the offenders (1,638 of 2,570) currently serving an LWOP sentence for a juvenile crime are in California (250), Louisiana (332), Pennsylvania (444), Michigan (346) and Florida (266).

Personalities in play: Justice Anthony Kennedy has long been the swing voter of the high court, and in the preceding juvenile sentencing cases he swung in favor of shielding juvenile convicts. Kennedy wrote the majority opinions in both Roper and Graham.

Roberts, who was not a member of the court when Roper was decided, agreed with the majority that Graham’s LWOP sentence amounted to cruel and unusual punishment. But he disagreed with the majority that Graham’s case proved the necessity for a categorical ban on LWOP sentences for juveniles.

In a separate opinion, Roberts favored the notion that a juvenile’s age should be factored into sentencing on a case-by-case basis, a view he repeatedly expressed during oral arguments in the case last November. A “categorical conclusion is as unnecessary as it is unwise,” Roberts wrote.

James Duncan Davidson

Bryan Stevenson at TED2012: Full Spectrum, February 27 – March 2, 2012. Long Beach, CA. Photo: James Duncan Davidson

Arguing for both convicts in these cases is Equal Justice Initiative Executive Director Bryan Stevenson, who has without question emerged as the leader in the fight to curtail harsh sentences for juvenile offenders. Stevenson represented Joe Sullivan – now 35 and sentenced to life at 13 for rape – in a case that the court heard in tandem with the Graham case. The court did not render a decision in Sullivan v Florida, but the questions at hand in the case were resolved by Graham. EJI has been working since Graham to identify offenders with legitimate ground for relief under the ruling and help them appeal their sentences.

EJI’s LWOP work was at one time funded almost entirely by the JEHT Foundation, which was done in by Bernie Madoff’s Ponzi scheme. Recently, as JJIE has reported, a speech by Stevenson at the TED 2012 Conference this month helped garner EJI $1 million in new funding.

Alabama Solicitor General John Neiman will argue for the state in Miller, and Assistant Attorney General Kent Holt will argue for Arkansas in Jackson.

Supporters and opponents: There were notably less amicus briefs filed in tomorrow’s two cases than were filed in Graham. Among the organizations that passed on filing a brief thus far in tomorrow’s cases: The Council of Juvenile Correctional Administrators and the National Partnership for Juvenile Services.

The Juvenile Law Center filed on behalf of Miller and Jacksons, as did Amnesty International and a group of family members who have lost relatives to homicides committed by juveniles. Two of the six groups filing on behalf of states against Terence Graham filed again in support of Alabama and Arkansas: The National District Attorneys Association and the National Organization of Victims of Juvenile Lifers.

Perhaps the most interesting names on any of the amicus briefs were those of James Alan Fox and John Dilulio, who signed onto a brief filed by juvenile justice researcher Jeffrey Fagan in support of Miller and Jackson. Fox and Dilulio forecasted a rising tide of violent juvenile offenders in the mid 1990s, and are widely blamed by reform advocates for helping to prompt a wave of get-tough laws that subjected more young offenders to adult courts and sentences.