![]()

As juvenile justice reforms take hold in California and youth arrests rates plunge, far fewer youth are being placed into the criminal justice system and prosecuted as adults.

Beginning in 2019, a new state law will halt criminal prosecutions of youth under 16 by prohibiting their transfer into the adult criminal justice system. This reform, championed by youth advocates and justice-minded leaders in the state Senate, will help curtail the well-documented harm of criminal processing, conviction and sentencing of youth.

California’s definitive shift away from the treatment of youth as adults — in both policy and practice — serves as a model to other states and presents an effective pathway to reform.

The newest transfer law promises to limit the number of youth facing adult court prosecution by ending the transfer of 14- and 15-year-olds and protecting them from the risks of criminal court conviction, which include lengthy prison sentences, reduced access to rehabilitative programming and lifelong felony records.

Now, all young teens will remain in juvenile court where they can benefit from a system predicated on rehabilitation and treatment. California’s juvenile justice system is resource rich, offering a range of treatment and rehabilitation options for youth under the jurisdiction of the juvenile court. For example, nearly every county operates its own secure juvenile hall, camp or ranch, and the state provides counties with hundreds of millions of dollars annually for local juvenile justice programming.

Maureen Washburn

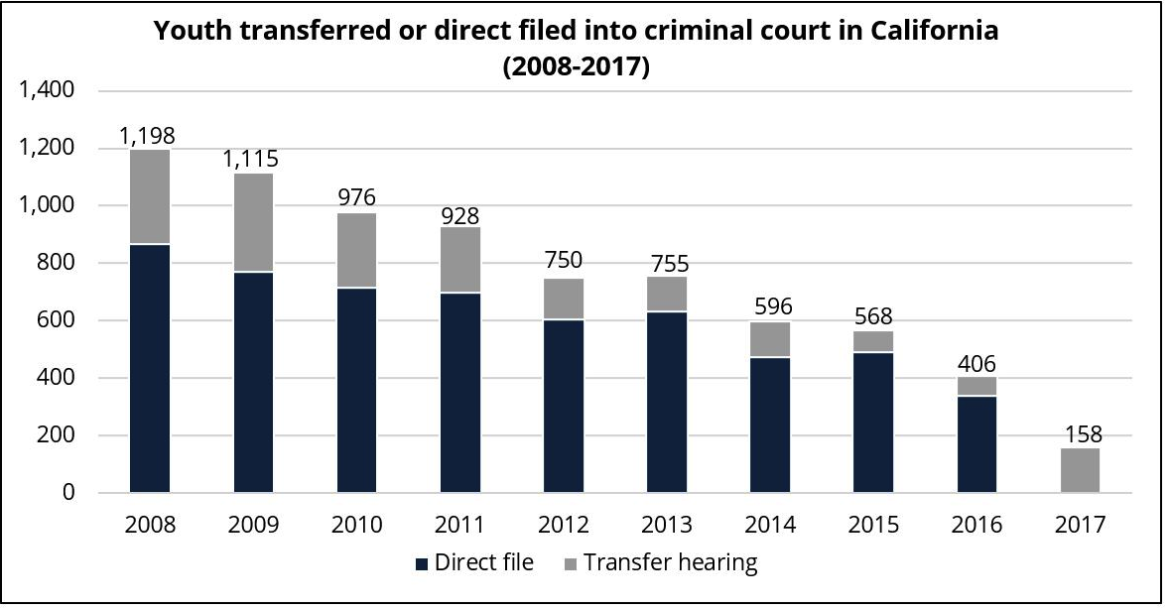

Over the past decade, California has seen a nearly 90 percent decline in the number of youth consigned to adult criminal court. This decline represents roughly 1,000 fewer youth facing traumatic and consequential adult proceedings each year.

California’s downward trend was most pronounced in 2017 when the state saw a 61 percent drop in the number of youth placed in criminal court in just one year. This shift coincided with the implementation of a groundbreaking ballot initiative, Proposition 57, which ended the practice of direct filing charges against youth in criminal court at the sole discretion of a prosecutor. In the absence of direct file, prosecutors could only seek adult prosecutions in youth cases through a process known as a transfer hearing in which a juvenile court judge determines whether a youth should remain in the juvenile justice system or be placed in criminal court.

Transfer hearings require prosecutors to successfully demonstrate that a youth should be tried in adult court in spite of their life circumstances, treatment needs and other mitigating factors, including the extent to which the juvenile system succeeded in meeting their needs in the past. Given these hurdles, the passage of Proposition 57 spurred monumental change in prosecutor practices, with many district attorneys seeking criminal court prosecution in far fewer youth cases. As a result, the end of direct file in late 2016 did not produce a commensurate increase in prosecutor-initiated transfer proceedings the following year. Instead, DAs sought adult court prosecution approximately half as often in 2017 as in 2016 (444 compared to 255).

While policy changes have helped bring about visible declines in the number of youth facing transfer in California, this promising trend is also attributable to youth themselves. In recent years, California has seen record-setting lows in its rate of juvenile arrests, including arrests for violent felonies. Since 2009, rates of felony arrest per 100,000 youth ages 10-17 have fallen 66 percent, tracking closely with declines in the number of youth at risk of adult court prosecution ( down 80 percent) and the number of youth ultimately placed in adult court (down 86 percent).

In fact, California youth are involved in the justice system at far lower rates than either their parents’ or grandparents’ generations. Nationwide youth arrest trends mirror California’s and are accompanied by other positive indicators of youth health and success, including lower rates of teen births and self-reported drug use and higher rates of high school completion.

Our nation’s adherence to the teenage “superpredator” myth resulted in an overbuilt juvenile justice system and far too many pathways into adult court. Yet today’s youth trends bolster juvenile justice reform efforts and allow lawmakers to re-examine the nation’s patchwork of adult court transfer laws, which include prosecutor-initiated transfer, transfer controlled by judges and statutory exclusions that automatically place certain types of youth cases in adult criminal court.

Although 36 states have recently passed laws placing stricter limits on the treatment of youth as adults, all 50 states and the District of Columbia still allow youth under 18 to be prosecuted in adult court under certain circumstances and four states automatically try 17-year-olds as adults (Georgia, Michigan, Texas and Wisconsin).

With its series of victories in the legislature and at the ballot, California has emerged as a model to reformers nationwide who seek to limit youth transfers. Other states must heed its example and capitalize on positive youth trends to abolish a practice that does measurable harm to youth, families and communities and fails to serve the interest of justice.

Maureen Washburn is a member of the policy and communications team at the Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice.

Pingback: Marshall Geisser Law | Far Fewer CA Teens Are Prosecuted as Adults