OP-ED: Juvenile Probation – Time to Take a Hard Look at What We Are Doing

|

It is evident we do not adequately hold ourselves accountable for the efficacy of our labor and the outcomes of the youth and families we intend to serve.

Juvenile Justice Information Exchange (https://jjie.org/page/282/)

In late September, Torri was driving down the highway with her 11-year-old son Junior in the back seat when her phone started ringing.

It was the Hamilton County Sheriff’s deputy who worked at Junior’s middle school in Chattanooga, Tennessee. Deputy Arthur Richardson asked Torri where she was. She told him she was on the way to a family birthday dinner at LongHorn Steakhouse.

“He said, ‘Is Junior with you?’” Torri recalled.

Earlier that day, Junior had been accused by other students of making a threat against the school. When Torri had come to pick him up, she’d spoken with Richardson and with administrators, who’d told her he was allowed to return to class the next day. The principal had said she would carry out an investigation then. ProPublica and WPLN are using a nickname for Junior and not including Torri’s last name at the family’s request, to prevent him from being identifiable.

When Richardson called her in the car, Torri immediately felt uneasy. He didn’t say much before hanging up, and she thought about turning around to go home. But she kept driving. When they walked into the restaurant, Torri watched as Junior happily greeted his family.

Soon her phone rang again. It was the deputy. He said he was outside in the strip mall’s parking lot and needed to talk to Junior. Torri called Junior’s stepdad, Kevin Boyer, for extra support, putting him on speaker as she went outside to talk to Richardson. She left Junior with the family, wanting to protect her son for as long as she could ...

It is evident we do not adequately hold ourselves accountable for the efficacy of our labor and the outcomes of the youth and families we intend to serve.

Juvenile justice advocates' fight to transform Connecticut from one of the only three states in the nation to prosecute 16-year-olds as adults to one of the leaders in juvenile justice reform wasn’t easy, but advocates say it provides a model for the two states left — North Carolina and New York — as they navigate if, and how, to make the change.

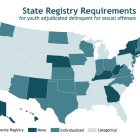

There is very little flexibility when it comes to determining who must register as a sex offender.

The ACLU of Ohio is asking the state’s highest court to stop the indiscriminate restraint of children in juvenile courts.

A punishment thought more appropriate for older students — suspension from school — is employed in pre-kindergarten and African-American preschoolers are suspended in wild disproportion to their numbers, the U.S. Department of Education revealed last week.

At Trenton Central High School in New Jersey, where the ceilings are literally crumbling and the auditorium is condemned, I wonder how anything gets done at all. What is it like to attend high school in a campus that is falling apart? Photographer Andrew Wilkinson examines.

LOS ANGELES — Antonio was only 14 years old when he was charged with two counts of attempted murder in April 2012. Because of his age and the fact that he had no prior record and because there were strong indications that he didn’t know his much older co-defendant was going to shoot anyone, he seemed to be a strong candidate to be tried in juvenile court. Inexplicably, his appointed lawyer failed to vigorously fight to have Antonio tried as a juvenile, failed to call witnesses or ask questions at a probable cause hearing where Antonio’s lesser culpability could have been argued and failed to ensure that Antonio’s probation report was accurate and complete, according to interviews and court records. As a result of this litany of legal missteps, Antonio’s case was sent to adult court — where he suddenly was facing 90 years in prison if convicted. Such problems are far from unique.

The first poem that really resonated with me was Etheridge Knight’s Hard Rock Returns to Prison from the Hospital for the Criminally Insane. Up until then I thought poetry was worthless. But to read its final lines while sitting in prison with a life sentence made the hair stand up on my arms.

“The fears of years, like a biting whip / Had cut deep bloody grooves / Across our backs.” I fully felt the horror that he wrote about, and the dreadful fear of acting in defiance in the face of overwhelming control and violence. Knight had discovered his gift for writing while in prison, and went on to become one of the nations most respected poets. The value of writing as an exercise in both self-connection and expression can’t be underestimated.