Lack of Expertise, Inadequate Funding Plaguing Mental Health Delivery to Nation’s Juvenile Justice System

|

Are young people in the juvenile justice system with mental health disorders being properly diagnosed and treated?

Juvenile Justice Information Exchange (https://jjie.org/series/mental-health-2/page/3/)

It presents one of the most vexing challenges facing our nation’s juvenile courts and corrections systems: how to treat, supervise, punish or just plain cope with troubled teens whose delinquent behaviors are connected to or caused by emotional disturbances and mental health problems. Many recent studies concur that two-thirds or more of all youth confined in juvenile facilities nationwide suffer from one or more mental conditions, and perhaps one in five suffers from a serious and debilitating mental illness – far more than in the general youth population. Awareness of the mental health/juvenile justice challenge is rising. Still, all across the country juvenile justice systems are struggling to respond.

Are young people in the juvenile justice system with mental health disorders being properly diagnosed and treated?

In a pair of feature stories published yesterday, (on Georgia's reform efforts and issues and two young men in the system) JJIE described two modes of intensive at-home treatment that show great promise to improve outcomes for emotionally disturbed youth in the delinquency system, both of which cost far less than incarceration or treatment in a residential treatment center.

Georgia leaders are embracing reform in juvenile justice, but serious gaps and significant roadblocks still prevent many emotionally-troubled youth from receiving the best and most cost-effective care.

Over the past three decades, adolescent development scholars, criminologists and mental health practitioners have achieved a breakthrough – or rather two breakthroughs. They have developed two different approaches to the care and supervision of troubled and delinquent children that consistently work better and cost less than correctional confinement and other commonplace services. One approach, which involves intensive and highly-regimented family therapy delivered to young people in their own homes, has been rigorously tested in scientific evaluations and repeatedly yielded substantial and statistically significant reductions in recidivism and treatment/confinement costs. The second – known as wraparound – targets youth with serious emotional disturbances, and it assembles a team of caring adults to devise an appropriate mix of community-based services in lieu of placing the child into a residential facility. Numerous studies show that wraparound, too, improves behavioral health and reduces involvement in the justice system – and does so at a fraction of the cost of confinement or residential treatment.

A Children’s Law Center report released last week finds that young people in Washington, D.C. are not receiving speedy assistance from the District’s mental health services.

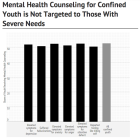

In 2010, the federal Office of Juvenile Justice Delinquency Prevention released results from the first-ever nationally representative survey of youth confined in juvenile justice facilities. However, because interviews were conducted in 2003, the findings beg the question: What changes have occurred since 2003 in mental health care for confined youth?

How many young people confined in the juvenile justice system need treatment for mental health and substance problems, and how well are those needs being met? The Survey of Youth in Residential Placement (SYRP) – the first-ever national survey of youth in juvenile custody – offers a detailed, if slightly dated, window into these issues using information obtained from young people themselves. See related story here. Conducted in 2003, SYRP gathered data from a nationally representative sample of youth housed in state and local juvenile facilities. Not released until 2010, the SYRP data show that many young people confined in juvenile facilities had experienced trauma, and most suffered with one or more mental health or substance abuse problems. Yet many confined youth received no counseling in their facilities.

Early in 2000, after a groundbreaking study revealed epidemic levels of mental illness among detained youth in Cook County – plus a severe lack of counseling and treatment – the Illinois Department of Human Services launched an ambitious new Mental Health and Juvenile Justice Initiative.

A century after Cook County, Illinois launched the world’s very first separate court system for juveniles accused of delinquency, a study found more than half of the young people in the county's juvenile lock-up suffered from at least one mental health disorder.

How big a difference can new evidence-based treatment methods make in the cases of juvenile offenders with mental health problems? In Cook County, Illinois, juvenile court leaders decided to find out. Specifically, they agreed to participate in a randomized controlled experiment to test the impact of Multisystemic Therapy (MST) – a prominent new treatment methodology – against the court’s usual services for youth accused or adjudicated for juvenile sex offenses. The study, published in 2009, involved 127 youth accused of sex offenses and ordered by the court to attend sex offender treatment. Sixty-seven were assigned to MST, and 60 were assigned to Cook County probation department’s existing juvenile sex offender unit and required to take part in weekly sex offender treatment groups.