The National Juvenile Justice Network has announced its two annual awards.

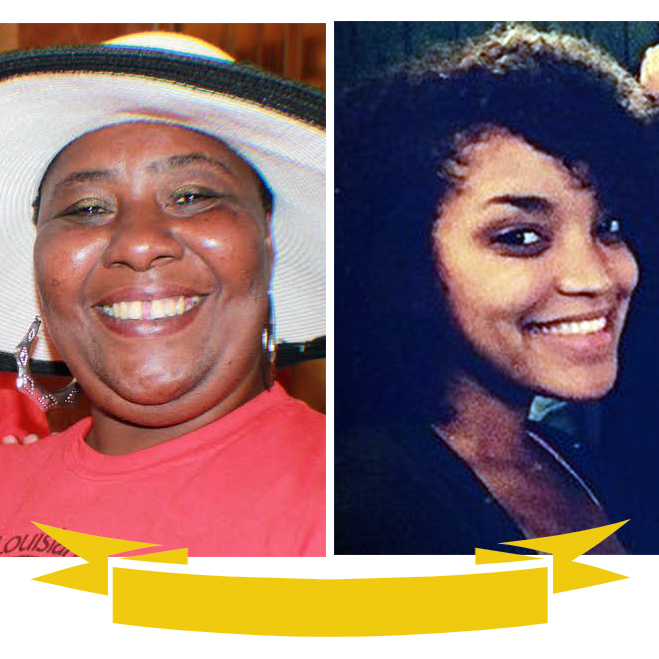

Verna Carr of New Orleans was awarded the Beth Arnovits Gutsy Advocate for Youth Award 2017. She first became involved with Family and Friends of Louisiana’s Incarcerated Children six years ago when her then-13-year-old son had faced multiple suspensions, which began his trajectory into the school-to-prison pipeline.

For more information about COMMUNITY BASED ALTERNATIVES, go to JJIE Resource Hub | COMMUNITY BASED ALTERNATIVES

Since then, she has advocated for 15 youth who have been facing prosecution in criminal court and meets weekly with young women detained at a juvenile detention facility.

Amber Evans of Columbus, Ohio won the Emerging Leader Award. She started working for the Juvenile Justice Coalition of Ohio in October 2015 as a part-time employee and transitioned to full-time in January 2017 as their policy and community engagement director.

Her nomination praises her for an “inside/outside” strategy that blends traditional organizing and policy spaces. She has also led direct actions on racial justice issues with the People’s Justice Project.

Both winners answered three questions for JJIE.

Verna Carr

Q. What made you decide to keep advocating after your son was taken care of?

I knew some of the children that were incarcerated with my son. After my experience with my son, I understood better how the system treated children so I needed to fight for them

Q. What would you say to other people thinking about volunteering?

It’s hard but rewarding in the end.

Q. What is your overall goal?

To make sure our kids have the life they deserve instead of having a life behind bars.

Amber Evans

Q. How did you end up in advocacy after getting degrees in journalism and library science?

In 2011, I became involved in student organizing at the Ohio State University following the emergence of Occupy Wall Street. Our group evolved into the Ohio Student Association (OSA). That following year, I was forced to challenge what role I would play as a journalist after experiencing one too many adverse situations within my academic cohort and among the beliefs of some of my instructors on the role of a journalist.

I felt that the dignity, voice and existence of low-resource communities, black families and people of color were being threatened under the guise of journalist objectivity. I could not sit idle as my university was contributing to the displacement of low-income families, and I refused to remain silent as our school newspaper chose to run an advertisement for a book promoting Muslim hate groups on campus.

In that same year, my stepfather entered into his fourth year of serving a five-year incarceration sentence. He was sent to prison in 2008, shortly before my grandmother was laid off from her 30-plus-year career with General Motors, following the economic crisis. This landscape of hardship led to an increase in the emotional and monetary support that I needed to provide for my family while processing my own childhood trauma.

I chose to take a step back from journalism and student organizing to reconnect with my community and pursue library sciences. Growing up, the library was my safe haven. A place for new beginnings. I maintained a support role in student organizing when I could, between working multiple jobs and grad school, but I craved a guaranteed space to reach the directly affected demographics missing from the organizing world on OSU’s campus.

After a few years in the public library system, I became aware of the symptoms of systemic oppression that existed in what was once my safe haven: monochrome leadership, culturally inappropriate language to enforce rules, security officers doubling as correctional officers, the fear and inconsistent punishment of black teens and young adults.

I plugged back into organizing on a volunteer basis and was later hired on part-time by the Juvenile Justice Coalition (JJC). I was tasked with creating a youth-led pilot program for young people and families directly affected by the school-to-prison pipeline to weigh in and lead on solutions to the issues.

In January 2017, I was offered a full-time position with JJC to serve as the organization's first policy and community engagement director. Being a librarian is my dream job, but blending policy and organizing with directly affected communities is my calling.

Q. What is the hardest part of organizing?

Being a directly affected leader organizing directly affected people to become leaders is the hardest part of organizing. Providing consistent physical, emotional, direct service and follow-up support are crucial to reaching and sustaining engagement with this demographic. Unfortunately, the development of directly affected leadership by directly affected leaders unearths a lot of untreated trauma. In the present culture of organizing and rapid response, there is not a lot of support or creation of space and time to address this issue.

Q. What do you feel optimistic about?

I feel optimistic about the power of young people and the instincts of directly affected communities to know what they need to obtain power. In the words of Stokely Carmichael, "I place my own hope for the United States in the growth of belief among the unqualified that they are in fact qualified." I believe this also holds true globally, especially with the support of trauma healing and restorative justice practices in directly affected communities.