![]() Across the United States, surging COVID-19 cases are risking the health and safety of youth in juvenile justice facilities. In November, the Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice (CJCJ) released a report examining a summer outbreak inside California’s state-run youth correctional system, the Division of Juvenile Justice (DJJ).

Across the United States, surging COVID-19 cases are risking the health and safety of youth in juvenile justice facilities. In November, the Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice (CJCJ) released a report examining a summer outbreak inside California’s state-run youth correctional system, the Division of Juvenile Justice (DJJ).

Shortly after our report was released, a second outbreak sparked. As of Nov. 30, confirmed COVID-19 cases spiked by 20 youth in a single week (97 total youth cases to date). DJJ’s first COVID-19 crisis serves as a warning: Lawmakers and service providers must step up to protect our nation’s youth.

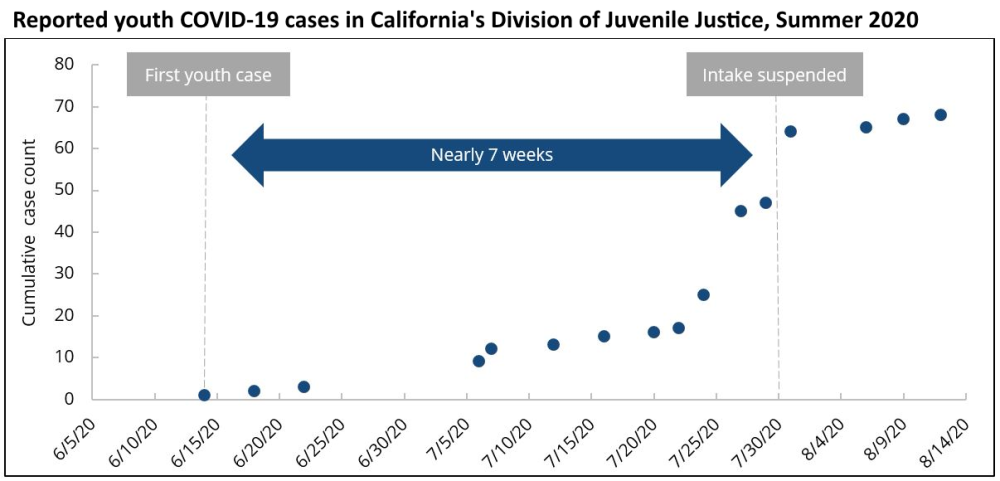

The DJJ, which is infamous for its violent conditions and history of neglect, endangered hundreds of youth by responding too slowly to the arrival of the virus. Infections grew sevenfold in a single month (July) and impacted roughly 10% of the youth population. As DJJ scrambled to contain the virus, it imposed harsh quarantine conditions and cut education and rehabilitative services.

Source: CDCR, 2020; Fremon, 2020.

Keeping young people safe amid the rising threat of COVID-19 requires swift action. Those living in close quarters are extremely vulnerable to the spread of infection. Yet common COVID-19 responses, such as isolation, can be harmful to mental health, especially for youth. To start, youth facilities need to significantly reduce their populations by halting or slowing intake and speeding up releases. They then need to develop a COVID-19 plan that protects all remaining youth from traumatizing isolation. The plan must ensure that youth stay connected to loved ones and continue to receive rehabilitative services.

COVID-19 can affect people of any age. Children and youth around the world have died or been hospitalized after developing an inflammatory condition that can result from COVID-19. As of Dec. 2, 528 people under the age of 25 have died of COVID-19 in the United States. Young people who survive a serious infection may still face a lifetime of health repercussions, such as irreversible damage to their lungs, heart or brain.

Youth in the juvenile justice system have been hard hit by COVID-19. As of Sept. 23, 1,805 youth in juvenile justice facilities had been diagnosed with the virus, according to The Sentencing Project. Their research shows that two of the 10 largest COVID-19 outbreaks in the nation took place in California — one at the Los Angeles County Central Juvenile Hall and the other at the DJJ Ventura Youth Correctional Facility, which sickened 42 youth.

Transfers continued, open dorms allowed

DJJ’s high case counts stem from its slow adoption of public health measures. For example, DJJ continued accepting youth from across the state for nearly seven weeks after recording its first infection. This decision ignored evidence that transferring incarcerated people spreads COVID-19. Earlier in the summer, San Quentin State Prison experienced a major coronavirus outbreak after state officials recklessly transferred incarcerated people into the aging facility. As a result, 28 incarcerated people have died and approximately 2,200 have been sickened in the prison. Yet even as news spread of the tragedy occurring at San Quentin, DJJ continued transferring youth into its own facilities.

Once COVID-19 arrived at DJJ, it spread quickly due to large youth populations within the institutions. Additionally, poor ventilation and communal living units increase the risk of infection. Each day, youth at DJJ eat, sleep and take part in recreation and programming within shared spaces. It is impossible for them to maintain safe physical distances.

At the height of its COVID-19 crisis, DJJ held approximately one-third of its population in open dormitory-style living units. In open dorms, youth share a bathroom and sleep on long rows of cots in an open room. Research has shown that COVID-19 infection rates are three times higher in open dorm living units compared to cell-based designs. In July, one of DJJ’s largest coronavirus clusters occurred in an open dormitory unit.

Maureen Washburn

DJJ also appears to have tolerated inconsistent mask wearing by staff and failed to conduct universal testing of young people. Flouting these important public health guidelines may have further contributed to the rapid spread of COVID-19 within DJJ. The agency’s COVID-19 response also exposed youth to the harmful impacts of isolation while restricting therapeutic services.

In the spring, as COVID-19 cases rose around the world, DJJ halted or severely limited many rehabilitative programs. Youth at DJJ already experienced long hours without structured supports prior to the pandemic. Beyond work or school, youth often spent hours playing cards or watching television in their living units’ common areas. Therapeutic groups were conducted by correctional staff. DJJ’s high school system failed to build basic proficiency among its students. DJJ had a poor track record in providing quality services to support youth development. Given its severe shortcomings, additional cuts to programming are deeply concerning.

Youth across the U.S. are experiencing COVID-19 isolation, with families and schools navigating new ways to ameliorate its negative effects. A national survey by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention finds that about half of young people ages 18 to 29 experienced anxiety or depression symptoms in a given week since April 2020 — higher than any other adult age group. Young people in the justice system are particularly vulnerable given the prevalence of traumatic experiences and the extent of their isolation.

Prior to the pandemic, youth in DJJ’s single-cell living units spent more than half of each day in isolation. As DJJ’s summertime outbreak worsened, youth spent long hours in hot cells as entire living units were placed under quarantine. Youth at DJJ have long experienced isolation from loved ones with 48% of youth sent to DJJ placed in facilities that are over 100 miles from their home county. Restricted visitation further disconnects youth from their families and communities.

Renee Menart

DJJ and other youth correctional institutions must implement precautions that prioritize young people’s mental health alongside physical well-being.

The health and safety risks at DJJ are inherent to large congregate institutions. Long before the threat of COVID-19, violence, poor programming outcomes and dilapidated facility conditions showed the cracks in California’s state-run youth correctional system. COVID-19 exacerbates these risks. This disease has made clear that we must reduce the populations inside youth facilities.

Across the country, correctional facilities are safely releasing people and reducing admissions to combat the spread of COVID-19. States and counties must follow suit by reducing the number of confined youth in their care.

DJJ’s failure to prevent an outbreak serves as a grim warning. An outbreak affects all youth, whether or not they contract the disease. It also devastates their loved ones. Without swift action to prevent further outbreaks, justice-involved youth are vulnerable to COVID-19 and its surrounding harm: The fear of getting sick. The psychological harm of isolation. Separation from loved ones. The potential physical toll of serious infection.

Living through a pandemic in a juvenile justice facility will leave its mark on thousands of young people who most need support and protection. We must all learn from this initial outbreak and protect our nation’s most vulnerable youth.

Maureen Washburn is a member of the policy and communications team at the Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice.

Renee Menart is a communications and policy analyst with the Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice in San Francisco.