Contents

Click on a topic below or scroll down for more information:

1. Comprehensive Reentry/Aftercare Models

2. Using Reentry Thinking to Guide Placement Decisions

3. Addressing the Challenges of Re-entering Youth

4. Reducing the Collateral Consequences of a Delinquency Adjudication

5. Supervision that Supports Youth

6. Using Evidence-based Treatment Programs in Reentry

7. Strengthening Federal Initiatives to Support Reentry

Reform Trends

Of the approximately 200,000 youth aged 24 and under released from secure juvenile facilities or adult prisons each year, 50 to 90 percent are estimated to recidivate.[1] For more successful outcomes, experts believe “aftercare supervision and services are key to promoting positive community adjustment” and recommend that reentry planning begin well before youth are released with continued support as youth reintegrate into their communities.[2] The information below details many reentry reform trends for intervening with youth in the justice system in a way that takes into account adolescent developmental needs.

1. Comprehensive Reentry/Aftercare Models

Below is information on the theoretical frameworks underlying many reentry/aftercare models as well as examples of comprehensive reentry/aftercare models. Experts recommend that all frameworks be supplemented by the “risk-need-responsivity” principles that should help to guide case planning, reentry planning, and service/supervision decisions.

A. Theoretical Frameworks for Developing Reentry/Aftercare Models

It is important to have a theoretical framework for the reentry or aftercare model that is based on the best available research, and knowledge of effective practices. The framework is used to guide reentry interventions.[3] Below are several frameworks that have been used:

1. Balanced and Restorative Justice (BARJ)[4] This theoretical framework balances the traditional juvenile justice needs for sanctioning, rehabilitation, and increased public safety with the overarching goal of restoration of victims and communities. The BARJ framework is three-dimensional – focusing on restoring victims, offenders, and communities:

-

- Youth who have committed offenses are obliged to acknowledge the harm they have caused the victim and make amends to redress harm to victims and communities through actions such as community service, apologies, and restitution. Once youth are able to take responsibility for their actions, it is believed that they are more likely to make better decisions in the future.

- Members of the youth’s community are responsible for creating the conditions necessary to facilitate their reentry into the community. This includes assisting youth in areas such as competency and skill development. Helping youth to successfully re-enter will, in turn, help to build a safer community.[5]

Strategies: Administrative — BARJ

Indiana

- Indiana’s Division of Youth Services established a restorative justice project within each correctional facility to facilitate community involvement and hold youth accountable for their actions.

- Each correctional facility partners with community organizations such as Habitat for Humanity and the Salvation Army so that youth in the facility can participate in community service projects.

- Restorative Justice Conferencing is being implemented to bring together victims, family members, and youth who have committed offenses in order to acknowledge the harm that was done to the victims and the community while holding the youth accountable for their actions.[6]

Philadelphia, PA

- The City of Philadelphia Mural Arts Program partners with the City of Philadelphia Youth Violence Reduction Partnership and other city organizations to provide youth in trouble with the law with the opportunity to create art while incorporating the concepts of restorative justice. They work with youth coming out of juvenile facilities, youth on probation, and young adults who have been involved with the justice system as well.

- The program emphasizes “reentry, reclamation of civic spaces, and the use of art to give voice to people who have consistently felt disconnected from society.”[7]

- The “Guild” section of the program is a paid apprenticeship program in which the participants are mentored by professionals and trained in activities such as wall and mural preparation and restoration and building repair.

- The activities youth work on are located throughout Philadelphia to give participants the chance to reconnect with and commit to their city.

- The recidivism rate for Guild participants is 13.5% compared to a national average of 67.5%.[8]

Strategies: Legislative — BARJ

Pennsylvania

- The Pennsylvania General Assembly established balanced and restorative justice as the philosophical and theoretical framework for Pennsylvania’s juvenile justice system in 1995 through their amendment of the purpose clause of Pennsylvania’s Juvenile Act.[9]

- While it does not mention “reentry” specifically, the act, as amended, states that it is Pennsylvania’s intent to provide youth committing delinquent acts “programs of supervision, care, and rehabilitation which provide balanced attention to the protection of the community, the imposition of accountability for offenses committed and the development of competencies to enable children to become responsible and productive members of the community.”[10]

2. Strain, Social Learning, and Control Theories

The Intensive Aftercare Program model is based on a theoretical framework that incorporates social control, strain, and social learning theories. Below is a brief description of each of these theories:[11]

-

- Social Control Theory: Social controls deter individuals from committing delinquent behavior. Therefore, individuals who lack socialization are more likely to commit crimes.

- Strain Theory: Delinquency occurs because there is a real or anticipated blocked opportunity to achieve socially accepted goals (such as achieving economic success).

- Social Learning Theory: Delinquency is a product of social interaction. Therefore, if individuals regularly engage with individuals who are deviant, they too will be likely to engage in deviant behavior.

3. Strength-based Perspective

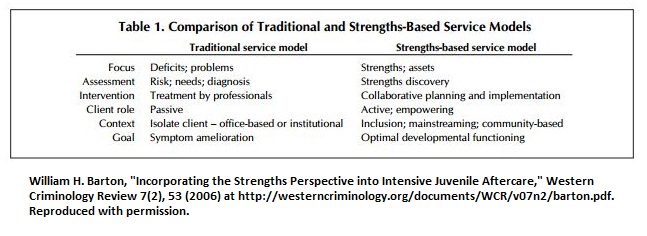

The strength-based perspective is based on the principles that: all youth, families, and communities have strengths; clients are best served when staff collaborate with them; and “every environment is full of resources.”[12] Pursuant to strength-based theory, youth are more likely to change when they are fully engaged as partners in identifying and developing their strengths rather than being a passive recipient of change efforts by others.[13] The strength-based approach “necessitates a move away from a deficit-based model focused on the “‘problems’ with youths.”[14] Two theories incorporating the strengths-based perspective, positive youth development and positive youth justice, are discussed below.

The table below provides a comparison of Traditional and Strength-based Service Models:

Positive Youth Development (PYD)

- Positive Youth Development (PYD) is rooted in research on adolescent development which has found that adolescents’ brains continue to develop through their mid-20s, making them quite malleable and capable of positive development.[15]

- PYD also builds on recent studies of adolescent development that have determined that most youth are resilient, meaning they are able to thrive and develop even in the face of multiple risk factors. PYD is strength-based, rather than deficit-oriented.[16]

- PYD promotes youth’s positive development through competency building and positive connections with peers, adults, and community institutions. It also stresses fostering a supportive, empowering environment that includes high expectations for positive behavior and promotes activities that allow the youth to build skills, have challenging experiences, and be exposed to new social and cultural influences.[17][/tab]

Positive Youth Justice (PYJ)

- Positive Youth Justice (PYJ) is a method of adapting Positive Youth Development for juvenile justice-involved youth. It requires policymakers, program developers, and practitioners to focus on developing two core assets in youth: [18]

- learning/doing through methods such as developing new skills and competencies, actively using the skills, taking on new roles and responsibilities, and developing self-confidence; and

- attaching/belonging through actions such as becoming an active member of pro-social groups, enjoying the sense of belonging, placing a high value on service to others, and being part of a larger community.[/tab]

Strategies: Administrative

District of Columbia

- The D.C. Department of Youth Rehabilitative Services (DYRS), has “infused” the PYD and PYJ principles into “all aspects of DYRS culture – from staff training, to youth programs, to the agency’s accountability mechanisms.”[19] DYRS “has adopted the PYJ framework as its core evidence-based model for providing supports, services, and opportunities” to young people.[20]

Oregon

- The Oregon Youth Authority uses PYD principles to guide its work in order to “create a culture in which all individuals – staff and youth – work collaboratively to discuss issues, resolve problems, and develop pro-social solutions and behaviors.”[21]

B. Examples of Comprehensive Reentry/Aftercare Models

Comprehensive models have been evolving over the past two to three decades and the data on their effectiveness has been equivocal. It has been difficult to discern their effectiveness in large part because of the difficulty in implementing the models. Below we have detailed several different models of comprehensive reentry and aftercare for youth.

1. Effective Practices for Community Supervision Training (EPICS)[22] This program was developed by criminal justice experts at the University of Cincinnati. It can be used with adults and youth and targets high and moderate-risk probationers. Probation/parole officers are trained to develop a collaborative relationship with the adult or youth, address criminogenic factors with them, and teach them pro-social and problem-solving skills. Probation/parole officers are trained to work four components into meetings with their supervisees:

-

- Check-in – building rapport with youth and discussing challenges and compliance.

- Review – discussing prior sessions with youth and steps taken to apply new skills.

- Intervention – identifying continuing areas of need, thinking patterns that can lead to offending, and new skill development.

- Homework and Rehearsal – assigning youth tasks in which to apply the new skill, role-playing with the new skill, and giving youth instructions to follow before the next visit.

Strategies: Administrative

Ohio[23]

- The Ohio Department of Youth Services adopted the EPICS model as an evidence-based framework for interacting with youth on parole.

2. Intensive Aftercare Program (IAP)

The IAP model focused on “the identification, preparation, transition, and reentry of ‘high-risk’ juvenile offenders from secure confinement back into the community in a gradual, highly structured, and closely monitored fashion.”[24] This model was one of the first to acknowledge that effective aftercare planning must begin from the moment a young person enters a correctional facility.[25] Two of the central components of IAP are as follows:

-

- The “overarching case management process” was a central element of IAP. This process uses risk and needs assessments to match youth with services that are appropriate to their needs and ensures a systematic “continuity of care” for the youth from the time they are incarcerated to their release into the community.[26] This process continues to be used in many reentry programs today.

- “Continuity of care” refers to the sequenced process of care where treatment and services are linked together from a juvenile facility through aftercare. Maintenance of the five components below are necessary in order to increase the likelihood of a successful transition from a juvenile facility to the community. [27]

- Continuity of control refers to the extent of structure and control experienced in a facility or a program. It is recommended that structure and control be gradually reduced prior to release in order for youth to prepare for life outside of the facility.

- Continuity in the range of services is important because once youth are released from a facility, they often lose services that were available to them that are essential to their success, such as medication and mental health care.

- Continuity of service and program content refers to programming such as education, vocational and social skills, treatment, behavioral management, etc. The reinforcement of what youth have accomplished in placement after they are released is thought to increase success in the community.

- Continuity of social environment emphasizes the importance of pro-social support in both facilities and in the community once youth are released.

- Continuity of attachment refers to youth developing positive relationships with people in the community. This component is commonly fulfilled with mentorship programs in the community.

Further details on the IAP program are available in the JJIE Hub: Reentry — Key Issues section.

3. Missouri Approach

Missouri’s unusual approach to juvenile justice is considered by many to be a national model. As a result of dangerous conditions that existed for years in their large juvenile correctional center, the Booneville Training Center, Missouri closed Booneville in 1981 and opened smaller, more therapeutic facilities across the state in which aftercare was a key component. Below are details regarding the Missouri approach:[28]

-

- Youth go through a risk assessment process and are placed within facilities based on the results. Missouri’s Department of Youth Services (DYS) has built a continuum of care to address youth with varying risk and needs profiles.

- The majority of adjudicated youth are not sent to the state youth corrections agency but are released, placed in diversion programs, or placed in local youth correction facilities.

- Even in secure facilities, Missouri DYS tries to foster a humane, youth-friendly environment. There are no cells, few locked doors, and little security hardware.

- The Missouri Approach emphasizes group treatment, case management, a youth-friendly environment, well-trained staff, double coverage (having two staff present during any interaction), education and training, individual and family training, keeping youth in facilities close to their place of residency, and aftercare.

- Aftercare is a key component in the Missouri Approach. Youth leaving facilities are placed on aftercare care status for 3-6 months after release, where they follow an aftercare plan developed prior to their release, and meet with their service coordinator.

- Around 40% of those in aftercare are assigned a “tracker” who meets with them several times a week to monitor their progress, provide informal counseling, and help them with job searches.

- In 2011, the recidivism rate (defined as youth who either return to DYS or become involved in the adult correctional system within 12 months after aftercare is complete) was 14.4%.[29]

4. Ohio’s Reentry Continuum[30] Ohio undertook a significant reform of its reentry services in the late 2000s, following the Stickrath lawsuit against the Ohio Department of Youth Services (ODYS) for dangerous conditions of confinement. As a result, ODYS developed a new reentry master plan for youth in 2009 that included the following provisions:

-

- Adoption of the Effective Practices in Community Supervision (EPICS) model for parole staff interactions with youth.

- Implementation of the Ohio Youth Assessment System (OYAS) to assess risk, identify needs, and target treatment programming for all youth on parole.

- Youth are assessed at many points in the juvenile justice process, including every six months or after any significant incident occurs, while in a juvenile facility and after release to parole.

- Probation officers are required to administer the OYAS 90 days prior to the youth’s release date as a basis for the youth’s release plan.

- Development and implementation of a number of family and youth engagement tools.

- Reduction of the length of stay parole guidelines for low- and moderate-risk youth. Research has shown that recidivism rates increase for these youth the longer they remain on parole.

- Development of the Pre-Qualified Vendors Initiative – an effort to reinstate contracts for non-residential services, which had been eliminated over the past several years due to budget cutbacks, and provide a mechanism to purchase services for youth on a case-by-case basis.

- Judicial collaboration with parole leadership to put in place a process for recommending youth for special discharge if they have received the maximum benefit that they can from parole.

- Support and encouragement of reentry courts with counties interested in this option.

- Participation in the Ohio Ex-Offender Reentry Coalition, which provides guidance to the state, local agencies, and communities on expanding and improving reentry efforts, emphasizing preparation for reentry and targeting the barriers offenders face to successful reintegration in the community.

- Development and implementation of discharge agreements, which are agreements between the youth, their family, and the probation officer that will serve as a final checklist to make sure that the youth being discharged has been connected to any needed services and resources for support.

- Establishment of the Youth Offender Release Identification Card (YO-RIC). Youth are issued this card in the facility and upon release it can be exchanged at the local Bureau of Motor Vehicles for a state I.D.

Strategies: Legislative

House Bill 130,[31] passed by the Ohio legislature in 2008, established the Ohio Ex-Offender Reentry Coalition (OERC), whose mission is to reduce recidivism, maintain public safety, and reintegrate individuals into society.[32] This was another impetus for reentry reforms undertaken by the Ohio Department of Youth Services (ODYS) discussed above.

Strategies: Litigation

In 2008, S.H. v. Stickrath, a class action lawsuit, was filed against the Ohio Department of Youth Services (ODYS).

- Plaintiffs alleged that youth were subjected to abusive, inhumane, and illegal conditions, policies, and practices. The report of the fact-finding team authorized by the court established that the conditions of confinement within ODYS facilities fell below constitutional and statutory standards.[33]

- Under the terms of the 2008 settlement agreement, ODYS agreed to “a comprehensive continuum of care in a regionalized services delivery system, a system of monitoring, youth-focused care, quality treatment interventions, engagement of families, education and vocational training of youths in the system, a grievance system, access to advocates/attorneys, strong reentry programs, and a fair and effective release process.”[34]

- Regarding reentry, the settlement agreement further stated that “Reentry efforts should begin at the time of admission and utilize a wrap-around case management function which includes residential options for youth who cannot return home to their families.”[35]

5. Pennsylvania’s Comprehensive Aftercare Model: Probation Case Management Essentials for Youth in Placement[36] This model is based on the work of Pennsylvania’s Comprehensive Aftercare Reform Initiative, which was supported by funding from the Pennsylvania Commission on Crime and Delinquency (PCCD) and the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation as part of the Models for Change Initiative.

-

- In January 2005, Pennsylvania’s multi-agency Aftercare Working Group signed a “Joint Policy Statement on Aftercare” which laid out the principles of a comprehensive aftercare system.[37]

- The joint policy statement committed the state to 17 concrete goals relating to aftercare – including early assessment and planning, multi-agency collaboration, documentation and records transfer, visitation and monitoring, judicial oversight hearings, and school reintegration.[38]

- The PCCD, with some funding from Models for Change, funded five 3-year pilot demonstration projects in five different jurisdictions in Pennsylvania to focus on different elements of aftercare reform.[39]

- A group of administrators and staff of these demonstration projects used what they learned to help develop Pennsylvania’s comprehensive aftercare model, known as the Case Management Essentials (CME), to operationalize the goals of the state’s joint policy statement.[40]

- CME focuses on a single plan for reentry developed by the probation department for each youth to guide and ensure the continuity of case management for youth in placement and after release.[41]

- CME includes a set of practices for assessing, planning, and managing cases under juvenile court jurisdiction and reporting outcomes.[42]

- The probation officer must develop the plan for each youth based on the post-release expectations for the youth and must help to effectuate it by collaborating with the school district, the facility, the youth’s family, and other partners that can support the youth.[43]

6. Philadelphia Reintegration Initiative

The Philadelphia Reintegration Initiative was a multi-agency effort to better prepare youth in juvenile facilities for life after discharge.[44]

-

- The program worked to align the academic standards in public schools in Philadelphia with those in correctional facilities in order to lower the dropout rate of youth involved in the juvenile justice system.

- The initiative outlined recommendations regarding training programs within the facilities, including offering practical training (auto, culinary, etc.) in areas that are in high employer demand and structuring training based on standardized curricula employers would recognize.

- Released youth were referred to the “Work Ready” program within the community that provided support to youth along three pathways – education, employment, and empowerment.

- These efforts were aimed at improving aftercare, reducing recidivism, and preparing youth for productive lives once they are released from the juvenile justice system.

- In 2008, 31% of the youth released from placement received a high school diploma, GED or both; 84% of youth discharged from reintegration services enrolled in school or participated in career training; and 37% of returning youth were employed at some point during the reintegration process.[45]

- The initiative had ended by 2010. The work that was done with placement providers, however, led to the establishment of the Pennsylvania Academic & Career/Technical Training Alliance (PACTT), a program aimed at making improvements to workforce development and education within youth facilities.[46]

7. Reentry Courts

Reentry courts manage a youth’s return to the community from an out-of-home juvenile placement. It involves using the court to monitor a youth’s reentry progress.

-

- Reentry courts operate on a model similar to other problem-solving courts such as drug courts. They use the authority of the court to monitor the youth’s progress, ensure they are provided the necessary services and support, and apply graduated sanctions and positive reinforcement to keep the youth on track.[47]

- Little research exists to demonstrate the effectiveness of youth reentry courts in reducing recidivism or reintegrating youth back into the community. The U.S. Office of Justice Programs is currently researching nine sites from around the country but only one, West Virginia, targets youth reentry.[48]

- Juvenile reentry courts initially received funding through the federal government’s Serious and Violent Offender Reentry Initiative (SVORI) and continued funding is now available through the Second Chance Act.[49]

Strategies: Administrative

Marion County, Indiana[50]

- This reentry initiative was funded by the Department of Justice’s Office of Justice Program’s Serious and Violent Offender Reentry Initiative (SVORI) and began operating in 2003. It was focused on youth returning from locked facilities to one of three high-crime neighborhoods in Indianapolis. A non-profit managed care contractor was responsible for all the case management services. The juvenile reentry court was committed to frequent oversight and enforcement hearings. Marion County currently only operates a reentry court for adult offenders.[51]

San Francisco, California[52]

- San Francisco’s Reentry Court was established in 2009 as a Second Chance Act National Demonstration Act Project Site. The program provides comprehensive reentry case planning and aftercare services for youth returning from out-of-home placements. Youth, their families, and a team of individuals working for the reentry court collaborate to develop a reentry plan which they each sign and jointly present to the judge. Initial contact between the youth and the reentry team starts at the youth’s disposition; three months prior to release, the plan is finalized. When this program started in 2009, the recidivism rate was 69% for reentry youth. By 2014, that rate had decreased to 13%.

West Virginia[53]

- West Virginia started a three-county juvenile reentry court pilot program in the state’s 21st Judicial District in 2000, which was likely the nation’s first juvenile reentry court. Funded later by SVORI, it was expanded to cover ten mostly rural counties in the northeastern region of the state. This program was a state-local partnership in which the WV Division of Juvenile Services provided enhanced supervision and case management to high-risk youth and local courts provided oversight through monthly court hearings to review progress and enforce conditions. [West Virginia currently only operates a reentry court for adult offenders.][54]

8. Strength-Based Wraparound Services

In this model, a support team works with the youth’s family to plan and implement services that are “community-based, tailored uniquely to each youth and family, culturally competent, coordinated among agencies, flexible, built upon the strengths discovered in each youth and family, and based on an unconditional commitment to provide services.”[55]

Strategies: Administrative

Dawn Project[56]

The Dawn Project serves children with behavioral disorders and their families to provide community-centered support in Marion County, Indiana.

- The project involves the families in each level of care; provides children with culturally competent, coordinated, and uninterrupted care; and emphasizes early intervention, strength-based, and value-based care.

- The target population of this program is youth between the ages of 5-17 who reside in Marion Country, meet the criteria for a serious emotional disturbance, and are involved in two or more child-serving agencies. This includes youth who are returning from a correctional facility.

- Coordinators, case managers, probation officers, teachers, and other team members work together with the goal of decreasing the need for formal system support for youth and their families.[57]

- Indiana Choices is now the formal title of the Dawn Project (although it is still widely recognized by the latter title).[58]

Wraparound Milwaukee

This program is recognized as a model for collaboration. It is a multi-service approach to meeting youth’s needs through the collaboration of the mental health, juvenile justice, child welfare, and education systems and pooled funding. It focuses on the strengths of the family, neighborhood, and community.[59]

- Services available to youth and their families include mental health therapy, substance abuse treatment, crisis intervention, in-home therapy, life skills development, medication management, child care, day treatment, and others.[60]

- Family involvement is seen as critical to the long-term success of the youth enrolled in the program. The families of youth are included in developing a “plan of care,” a crisis plan to help effectively manage stressful events, and identifying the strengths and needs of their family.[61]

- Around 44% of the youth served through Wraparound Milwaukee are youth who have been involved in the juvenile justice system.[62]

- Wraparound Milwaukee offers services to youth during their stay at juvenile correctional facilities, followed by services once they are released. A care coordinator from Wraparound Milwaukee works with the youth, family, and parole agent to facilitate a successful reentry back into the community.[63]

9. Targeted Reentry

-

- Targeted Reentry (TR) was a variant of the Intensive Aftercare Program developed by the Boys & Girls Clubs of America (BGCA). It connected youth held in juvenile facilities with Boys & Girls Clubs that provided recreational and other programming while the youth were still inside the facilities. Youth were then connected with BGCA back in the community as part of the reentry plan, with the local BGCA providing case management functions.[64]

- In 2003 and early 2004, BGCA, with support from OJJDP, introduced TR into four pilot sites in which they coordinated with state juvenile correctional facilities:[65]

- Mobile, Alabama with Mt. Meigs Juvenile Correctional Facility in Montgomery, Alabama.

- Anchorage, Alaska with the McLaughlin Youth Center, also in Anchorage.

- Benton, Little Rock, and North Little Rock, Arkansas with the Alexander Youth Center in Alexander, Arkansas.

- Milwaukee, Wisconsin with the Ethan Allen School in Wales, Wisconsin.

- A quasi-experimental evaluation of TR in four sites found low overall recidivism rates - between 23% and 40% were arrested for any new offense during the first 12 months following their release. However, the comparison groups’ outcomes were similar to or more favorable than those of the TR groups.[66]

2. Using Reentry Thinking to Guide Placement Decisions

Focusing on helping youth successfully re-enter the community starting from the time they become involved in the juvenile justice system can help to guide decisions every step of the way. Below are examples of reform trends to accomplish this.

A. Confining Youth as a Last Resort

Due to the harmful impact of confinement on youth — including increased rates of recidivism, harm to healthy youth development, reinforcement of negative peer associations, and isolation of youth from their family and communities — a focus on reentry encourages juvenile justice stakeholders to strive to confine youth only as a last resort and to limit confinement to higher-risk offenders.[67]

B. Considering Impacts on Youth Education When Making Placement Decisions

A focus on reentry can encourage probation officers to consider the educational needs of youth as a significant factor in making placement recommendations.[68]

- Juvenile probation officers are urged to exercise caution in recommending placements because the placement decision will have an impact on the youth’s reintegration into school. For example, a short-term placement may not be appropriate for a youth who needs intensive academic instruction, particularly if they have a disability, because the staff at such facilities may not be qualified to teach important core academic subjects.[69]

- The type and amount of education that a youth will receive in placement can vary significantly depending on where they are placed. Juvenile probation officers are urged to identify a youth’s educational needs and goals and make sure that if a placement is recommended, the facility can meet those needs and goals.[70]

C. Using Objective Risk Assessment Tools

Risk assessment tools are considered to be a critical element of reentry because they can both reduce the number of youth in out-of-home placement and help to more appropriately tailor interventions to youth in placement and back in the community.

- The National Council on Crime and Delinquency recommends the use of “risk assessments, screening instruments, and other tools to help systems shift youth to the lowest form of supervision needed to meet their needs, and, in some cases, to divert youth from the system entirely.”[71]

- Experts recommend that youth be periodically assessed throughout their contact with the system “from intake through placement and community supervision and services.” This will help to identify changes in risk as youth move through the system.[72]

Jefferson County, AL[73] New York City, NY[74] Ohio[75] Ohio developed and implemented the Ohio Youth Assessment System (OYAS) to assess risk, identify needs, and target treatment programming for all youth on parole. Philadelphia, PA[76]

Strategies: Administrative

For further strategies, see Evidence-Based Tools for Intervening with Youth:

Strategies: Administrative

Strategies: Legislative

Strategies: Judicial Initiatives

D. Using Validated Behavioral Health Screenings and Assessments

Over half the youth in the justice system have been found to suffer from mental health or substance use disorders, with that number rising to 64 percent for youth committed to secure facilities.[77] By implementing standardized screening and assessment tools for mental health and substance use disorders at key points in the juvenile justice process, appropriate youth can be diverted to behavioral health programs for treatment. To obtain the most successful outcomes, those youth requiring confinement should receive mental health and substance use treatment while they are in facilities, and continue this treatment without a gap once they re-enter their communities.

For further information and strategies see: Implement Standardized Screening and Assessment Tools

3. Addressing the Challenges of Re-entering Youth

Aftercare is intimately interconnected with the care youth receive while they are confined. For example, if youth have inadequate educational opportunities while in a juvenile placement, it will make it much more difficult for them to successfully re-enter school when they are released. Accordingly, within each subsection below, reform trends are broken down into two parts: (1) facility reforms – those reforms needed while youth are in facilities to pave the way for a more successful reentry; and (2) re-entry reforms – reforms needed to improve the process by which youth re-enter the community, and their experience in the community once they are released.

A. Improving Educational Opportunities for Youth

There is a strong link between poor academic achievement and delinquency.[78] Correspondingly, youth attachment to school leads to lower recidivism.[79] Unfortunately, many youths enter the juvenile justice system with significant educational deficits and often their educational needs are not addressed in placement or upon release. Below are suggested reforms to improve youth education in facilities and upon reentry.

1. Facility Reforms

Over 60,000 youth receive correctional education in juvenile justice facilities each year.[80] Education in juvenile facilities is often substandard and youth in adult facilities may receive no education at all.[81] Youth in short-term facilities also may fail to receive educational services or receive much less instructional time than youth in public schools.[82] Recommended facility reforms include the following:

-

- In a December 2014 letter to the nation’s chief state school officers and state attorney generals, the U.S. Departments of Education (ED) and Justice (DOJ) laid out five guiding principles to provide high-quality education in juvenile justice secure care settings:[83]

-

- A safe, healthy, facility-wide climate that prioritizes education;

- Necessary funding to support educational opportunities for all youth in long-term secure care facilities;

- Recruitment, employment, and retention of qualified education staff with the necessary skill set for teaching in juvenile justice settings;

- Rigorous and relevant curricula aligned with state academic and career and technical education standards that promote college and career readiness; and

- Formal processes and procedures to ensure successful navigation across child-serving systems and smooth reentry into communities.

-

- Additional needed facility reforms include:

-

- Ensuring that youth with disabilities and special education needs are identified and receive appropriate educational services as required under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act.[84] It is estimated that as many as 70 percent of youth in the justice system have learning disabilities.[85]

- Enabling English learners to meaningfully participate in the educational program as required pursuant to civil rights laws.[86]

- Safeguarding students from excessive use of seclusion and restraint which restricts their ability to access education.[87]

- Making a full continuum of educational opportunities available to youth to meet their individual goals, including pathways to achieve high school diplomas, GEDs, college preparation, and career and technical training.[88]

- Aligning correctional educational programs with state standards for public schools and local graduation requirements in order to improve educational quality. [89]

- Ensuring that correctional education credits transfer fully to community schools.

-

- In a December 2014 letter to the nation’s chief state school officers and state attorney generals, the U.S. Departments of Education (ED) and Justice (DOJ) laid out five guiding principles to provide high-quality education in juvenile justice secure care settings:[83]

2. Reentry Reforms

Over two-thirds of youth leaving custody do not return to school.[90] The US Departments of Education and Justice recommended in their recent Guiding Principles that “reentry planning should begin immediately upon a student’s arrival [into secure custody], outline how the student will continue with his or her academic career, and, as needed, address the student’s transitions to career and postsecondary education.”[91] Below are some of the reforms experts recommend to improve school reentry.

- Inter-Agency and Community Cooperation [92] Clearly identify the roles and responsibilities of the various agency personnel.

- Youth and Family Involvement

Include the young person and appropriate family members in the reenrollment process.

- Speedy Placement

Ensure that young people can enroll the same day or very soon after their release. This often requires improving record transfer practices and school reenrollment practices, which are discussed below.

- Improved Record Transfer

Youth often have difficulty returning to school because of missing school records and lengthy delays in the transfer of their school records[93] as well as perceived or actual confidentiality barriers to record sharing.[94] Recommendations for improvement include requiring states to set timelines for the transfer of records between schools for all students, including those in correctional facilities (such as transfer within seven days of request).[95]

- Improved School Reenrollment Practices

Additional barriers to re-enrollment that justice-involved youth face include lengthy and complicated processes for youth to reenroll in school and laws that some states have enacted to create obstacles for youth attempting to re-enroll.[96] Reforms that states have enacted to facilitate reentry include:

-

- reintegration teams (Maine);

- reintegration plans required 45 days before youth are released (West Virginia);

- the involvement of school district coordinators and the creation of educational “passports” (Kentucky);[97] and

- transition coordinators to work across juvenile justice and education systems to facilitate a youth’s timely re-enrollment.[98]

- Appropriate Placement

Ensure that the student is returning to an appropriate educational placement in the least restrictive environment based on the individual consideration of the youth rather than a policy, such as automatic placement in alternative programs for returning youth.

- Dropout Reengagement Programs[99] Helping youth find alternative pathways to continue their education has been a successful way to reengage both justice-involved and other youth who dropped out of high school. There is now an expanding network of local reengagement centers across the country that offer a range of services including individual academic assessments, opportunities for exploring different educational options, referrals to appropriate programs, and helping youth attain postsecondary education.

-

- The National League of Cities (NLC) has a Dropout Reengagement Network involving approximately 20 cities across the country that operate reengagement centers and programs.

- They recommend partnerships with school districts and community organizations. School districts sometimes take on the role of establishing reengagement centers as they have done in Portland, Oregon, and Reno, Nevada.

- They also recommend a cross-systems approach to pursue shared goals with juvenile justice, child welfare, and workforce development agencies.

- Community Based Workforce Programs

Youth and young adults face employment barriers due to their involvement in the legal system, but community-based workforce programs can help mitigate these challenges by providing support and opportunities. This report summarizes findings from a study on such programs, highlighting their strategies, partnerships, support services, funding, and outcome measurement.

Allegheny County, PA[100] District of Columbia[101] Pennsylvania[103] Washington California[109] Kentucky[110] Maine[111] Virginia Washington West Virginia[115] Pennsylvania The United States Department of Justice, Civil Rights Division, has brought many lawsuits to correct deficiencies in correctional special education programs under the Civil Rights of Institutionalized Persons Act (CRIPA).[116] Litigation on behalf of youth in correctional facilities has been initiated by the U.S. Dept. of Justice and other groups in 26 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico; most lawsuits have been filed since 1990. The majority of these cases have been brought on the basis of claims alleging a failure of correctional facilities to provide services to students as required under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). Below are two examples of this type of litigation:[117] Arkansas[118] South Dakota[119]

Strategies: Administrative

In 2004, New York City changed its practices to make re-enrollment easier by not removing students who leave for juvenile facilities from the school rolls but, rather, putting the students on a parallel list. This policy is called “dual enrollment” or “shared instruction.”

Strategies: Legislative

Strategies: Litigation

B. Improving Job Readiness

Many youth leaving juvenile facilities are older teens who will soon be looking for employment. As discussed in Key Issues, these youth can face barriers to employment as a result of their juvenile system involvement, so improving job readiness is particularly important for re-entering youth. Additionally, research has shown that “youths who complete programs that focus on structured learning, school achievement, and job skills are less likely to re-offend.”[120] Below are promising facility and reentry reforms that can improve youth’s job readiness:

1. Facility Reforms

Reforms to help youth improve their job readiness start with improved educational programs in facilities, as discussed above, as it will be easier for youth to get jobs if they are educated. Additional suggested reforms include the following:

-

- Make academic training relevant by linking it with career preparation.[121]

- Provide young people with skills that are valued and recognized by employers, and provide them with the opportunity to practice these skills in the facilities.[122]

- Provide youth with high-quality career technical training aligned with industry standards, programs of study for high-demand career paths, and testing for industry-recognized certifications, such as OSHA-10 for construction trades.[123]

- Provide youth with “soft” skills development, also known as “21st-century skills” – skills that teach youth to be presentable, reliable, and productive employees as well as skills in interviewing, problem-solving, and anger management.[124]

- Provide youth with access to and training in technology while confined and during reentry.[125]

2. Reentry Reforms

-

- The reentry process should give youth specific opportunities to build on the career/technical training skills they learned in placement.[126]

- Adjudicated youth should have access to internships, apprenticeships, and subsidized employment opportunities.[127]

- Many youths need continued on-the-job training when they leave the facility as well as other supports to enable them to be successful in the workplace, such as housing, mental health and substance use treatment, and child care.[128]

- Reforms such as the sealing and expungement of juvenile records can improve the ability of justice-involved youth to obtain employment.

Strategies: Administrative

Cambria County, PA[129]

Cambria County, a small, rural county with limited resources, was one of the five Pennsylvania county aftercare reform demonstration projects launched in 2005 as part of a broader statewide effort to improve aftercare. Cambria focused in part on job readiness and employment for re-entering youth through their “Learn to Work” project described below:

- Learn to Work is a collaboration between Cambria County and Goodwill Industries to create an assessment, job readiness, skill building, and employment opportunity program.

- Classroom instruction is complemented with paid work experiences for youth to attain job skills.[130]

- As of the end of June 2010, 75 youth had been served by Learn to Work, with the following results:[131]

- 36 (60%) successfully completed the program

- 18 (30%) found employment

- 66 (88%) increased their employability skills

- 53 (88%) acquired a more positive attitude

- 9 (5%) recidivated

- Cambria County has absorbed the program into its budget and it is still operating.[132]

- Learn to Work was replicated in neighboring Blair County.

Chicago, IL, Los Angeles, CA, and New Orleans, LA[133]

- Each of these cities is implementing “Youth Futures,” a multi-site project coordinated by the Vera Institute of Justice and funded by the U.S. Department of Labor, Education and Training Administration, to improve the education and employment prospects of justice-involved and at-risk youth living in high-poverty, high-crime communities.

- Youth Futures plans to serve approximately 900 youth aged 14 and over who are currently in (or in the last twelve months have been involved in) the juvenile justice system, particularly youth returning to the community from out-of-home placement.

- The following program components will be offered to youth: workforce development, education and training, case management, mentoring, restorative justice, and community-wide efforts to reduce crime and violence.

Hartford, CT

- Hartford helps returning youth to secure jobs by reserving spots in the city’s jobs program for justice-involved youth.[134]

Hudson County, NJ

- Youth Advocate Programs (YAP) runs a “Reentry Success Program” in Hudson County, New Jersey to which youth who have been incarcerated are referred.

- The key reentry services provided include case management, supported employment, educational and vocational support, and a program called Peaceful Alternatives to Tough Situations (PATTS).

- PATTS is an evidence-based curriculum that teaches youth interpersonal skills to help them become successful in the community and within the workplace, such as self-control, responsibility, forgiveness, conflict resolution, and other interpersonal skills.

- For more detailed information on this program click here.

King County, Washington[135]

- King County implemented the PathNet program in 2010, which coordinates a network of organizations including school districts, community colleges, and technical schools, to re-engage dropout youth. Youth take part in basic skills remediation, GED preparation, work and college readiness classes, and high school credit recovery options as well as vocational training and certification. Click here for further information.

Florida[136]

- Florida has five Job Corps Centers which provide vocational training and job placement services to youth who have completed their post-commitment services and have no further court involvement.

Pennsylvania[137]

- The mission of the Pennsylvania Academic and Career/Technical Training Alliance (PACTT), which is now run by the PA Dept. of Human Services, Bureau of Juvenile Justice Services (previously it was a project of the Pennsylvania Council of Chief Probation Officers) is to improve the education and job training that youth receive in juvenile justice facilities in order to facilitate their success in the community. PACTT has helped to make the following reforms:

- All facilities aligned with PACTT provide Career Technical Education (CTE) training and testing for one or more entry-level certifications that are recognized in the respective industries. Examples include ServSafe in culinary arts, OSHA-10 for construction trades, and the International Computer Driving License or Microsoft Office Specialist for administrative assistants.

- Due to PACTT’s work, CTE training in facilities has grown from approximately 25 programs in 8 facilities to 73 programs in 26 facilities by 2012.

- PACTT has developed an employability and soft skills manual to standardize the expectations for 27 key competencies, such as resume writing and conflict resolution.

- PACTT provides subsidized employment inside juvenile facilities so youth can practice their soft and technical skills and develop the confidence to apply for jobs upon reentry.

- PACTT is testing a model that will add a period of subsidized employment when youth re-enter the community.

- PACTT is also establishing connections with community colleges and other training centers so youth can continue their technical training and earn needed industry certifications.

Philadelphia, PA[138]

- The non-profit Philadelphia Youth Network operates “E3 Power Centers,” which are neighborhood centers that provide support to out-of-school youth and youth returning from juvenile justice placements along three pathways – education, employment, and empowerment. The employment pathway provides intensive work-readiness programming, including job-readiness training, subsidized internships, community service opportunities, and job search assistance.

Strategies: Legislative

Federal Initiatives

- The Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act, Job Corps, and Face Forward are federal grant programs designed to provide job training and employment services for youth involved with the juvenile justice system and young adults who were previously incarcerated.

St. Louis, Missouri[139]

- The St. Louis Agency on Training and Employment (SLATE) received funding through the Second Chance Act Reentry Project in 2013 for their You Only Live Once (YOLO) STL Reentry Program. The program was designed to serve 32 juveniles through a comprehensive evidence-based program design and partnerships with public and private agencies and major universities. Each participant will complete a minimum of 100 hours of service learning, 40 hours of job readiness, 125 hours of work experience, 125 hours of summer work experience, and 80 hours of mentoring.

Washington[140]

- Washington state passed legislation in 2010 (HB1418) establishing a statewide dropout reengagement system to provide educational opportunities and access to services for youth aged 16-21 that have either dropped out of school or will not be able to accumulate sufficient credits to graduate high school by age 21. It includes teaching work readiness preparation to enable the student to gain the skills necessary for employment. Juvenile justice case managers can refer re-entering youth to the program. The legislation was modeled on the PathNet program, supported by the Models for Change initiative.

C. Improving Mental Health and Substance Use Treatment for Youth

Over half the youth in the justice system have been found to suffer from mental health or substance use disorders, with that number rising to 63.7 percent for youth committed to secure facilities.[141] Unfortunately, mental health services typically available to youth in juvenile justice facilities are inadequate.[142] Substance use is especially significant because it increases the risk of future offending. Yet many justice-involved youth are not screened for the problem and do not receive treatment.[143]

To improve aftercare for youth, appropriate mental health and substance use treatment must begin while youth are in facilities and then continue without a gap when they leave. Additionally, youth should be treated humanely in facilities in ways that do not re-traumatize them, which can happen when youth are subjected to sexual abuse, isolation, or unsafe conditions.

1. Facility Reforms

Reforms to improve mental health and substance use treatment for youth in the juvenile justice system include the following:[144]

-

- diverting more youth from the system or from detention and secure confinement;

- implementing standardized screening and assessment tools for mental health and substance use disorders at key points in the juvenile justice process;

- using evidence-based and promising treatment programs with youth in facilities and in the community;

- treating youth that must be confined in small, humane, treatment-oriented facilities;

- improving the mental health education and training of juvenile justice agency and facility staff;

- enhancing family involvement in treating youth; and

- collaboration between the juvenile justice system, behavioral health system, and Medicaid agencies to coordinate treatment in confinement and in the community.

See the JJIE Hub: Mental Health — Reform Trends section of the hub for more detailed information.

Strategies: Administrative

Strategies: Legislative

Strategies: Litigation

2. Reentry Reforms

Youth reintegrating into the community need continuous supportive mental health/substance abuse treatment when leaving the facility, the continued involvement and support of their families, a plan for dealing with the possibility of relapse, and the potential for treatment beyond their period of supervision.

Reentry Planning to Ensure Continuous Mental Health and Substance Abuse Treatment

It is critical for youth with mental health and substance use disorders not to have gaps in their treatment. Recidivism often occurs within a few days of release and gaps in services have been found to significantly increase the risk of reoffending.[145] Additionally, relapse is typical for youth with substance use disorders. Youth with mental health and substance use disorders need access to treatment and any prescribed medication from the time that they leave the facility as well as beyond the period of their juvenile court supervision for long-term success.[146]

-

- Youth and families should be connected with long-term support and opportunities in the community that are based on their particular strengths and interests.[147]

- The aim is to develop a network of caring adults that youth in the community can be connected to and positive activities such as sports, the arts, employment, local churches, and volunteering.[148]

- More community-based substance use services need to be provided. The Pathways to Desistance study found that “only 30 percent of juvenile offenders with a substance use disorder ever received treatment for it in the community.”[149]

- Juvenile justice systems should identify drug treatment programs shown to be effective in reducing adolescent drug problems and adapt them for use in aftercare programs.[150]

- Drug treatment needs to be targeted in type and intensity to the needs of the youth so that those with diagnosable substance use disorders get intensive drug treatment and those with less severe issues get less intense preventive services.[151]

Montgomery County, Ohio[152] Montgomery County, Ohio is one of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s first ten pilot communities selected to create their six-step “Reclaiming Futures” model, which focuses on more drug and alcohol treatment, better treatment, and community connections beyond treatment. Montgomery County’s approach includes the following aftercare components: See JJIE Hub: Mental Health — Reform Trends for further examples of Administrative Strategies. Virginia[153] In 2005, Virginia passed legislation to ensure the continuity of necessary mental health treatment and services for youth leaving juvenile justice commitments. The legislation mandates the following:

Strategies: Administrative

Strategies: Legislative

Eliminating Gaps in Medicaid

Medicaid has emerged as a major source of mental health funding for youth in the juvenile justice system, many of whom are low-income.[154]

- Medicaid can provide eligible youth with access to health care, including mental health and substance abuse treatment, as well as needed medications.[155]

- Yet many youths who are eligible either are not enrolled or lose their benefits when they are placed in a juvenile facility.

- It is vital for these youth to have health benefits upon release because many are discharged from facilities without appropriate referrals for treatment, without health insurance, and with only a day or two of medication and no prescription for a refill.[156]

Below reforms are discussed to improve the situation for these youth:

Encourage Medicaid Enrollment

Below are policies that can speed up the process of Medicaid enrollment for youth in the juvenile justice system.

- “Presumptive eligibility” allows juvenile justice staff the authority to secure temporary eligibility for youth, pending a final Medicaid determination.[157]

- With “expedited Medicaid enrollment,” juvenile justice staff prepare Medicaid applications for youth leaving custody and the applications are expedited once the youth are released.[158]

Encourage Continuous Medicaid Coverage

- Youth are often abruptly terminated from the Medicaid rolls when they enter a juvenile justice facility because of the federal prohibition on Medicaid reimbursement of medical services for incarcerated individuals.[159]

- Yet states are not required to terminate eligibility. Rather, they can “suspend” a youth’s Medicaid enrollment instead of terminating it, which allows the young person to have their eligibility for Medicaid services restored immediately upon release.[160]

- If youth are terminated from Medicaid while confined, they must reapply upon release and it can take up to 90 days or longer to be reenrolled. This can result in long delays in getting needed medications and treatment, which jeopardize a youth’s successful reintegration into the community.[161]

Strategies: Administrative

Ohio[162]

- The Department of Youth Services notifies the state’s Medicaid agency — the Office of Medical Assistance (OMA) — when youth in their custody are Medicaid-eligible and are going to be incarcerated for less than twelve months. OMA can then suspend Medicaid benefits for those youth and restore them upon their release.

Oregon[163]

- The Oregon Youth Authority (OYA) entered into an Interagency Agreement with the Oregon Health Authority (OHA) to reduce gaps in medical coverage for youth. There is an OHA medical eligibility specialist in the central OYA office who can make eligibility determinations for youth transitioning in and out of custody, and coordinate other benefits as well.

- OYA notifies OHA when youth are incarcerated and Medicaid benefits are suspended, with youth eligible for benefits if they are released within a year from their incarceration date. Parents are notified to come to the benefits office within ten days of their child’s release in order for the youth’s benefits to be reinstated.

Washington[164]

- Washington State has made it a part of its youth reentry planning for Juvenile Rehabilitation Administration residential case managers and county detention facilities to screen youth for Medicaid eligibility 45 days prior to their release, and refer youth likely to be eligible to the Economic Services Administration (ESA). The ESA then expedites the applications.

Strategies: Legislative

Colorado[165]

- Colorado enacted legislation in 2008 (HB 08-1046) requiring juvenile facility personnel to assist youth in applying for Medicaid or the Children’s Basic Health Plan (CBHP) no later than 120 days prior to release (or, if they are committed for fewer than 120 days, then they must assist them as soon as practicable).

- The law also requires the Department of Health Care Policy and Financing to assist facility personnel and expedite the application process so that an eligibility determination can be made for youth prior to their release, and they can be enrolled immediately upon release if eligible.

Texas[166]

- Texas passed legislation in 2009 requiring the Texas Health and Human Services Commission (HHSC) to enter into a memorandum of understanding with the Texas Youth Commission to make sure that each youth who is committed or detained is assessed by HHSC for Medicaid and child health plan program eligibility before they are released.

- Juvenile justice staff now provide information about the youth to HHSC 45 days before their release, and HHSC staff determine whether a new application must be completed for the youth.

D. Improving Family Engagement

Families have often been viewed by juvenile justice stakeholders as part of the problem instead of the solution, creating obstacles to family involvement while youth are incarcerated and through their transition back into the community.[167] Yet research has confirmed the importance of family participation for juvenile delinquency outcomes.[168] Family involvement – defined as “empowering families, based on their strengths, to have an active role in a child’s disposition and treatment” – is crucial at every stage of the juvenile justice process. Below are suggested reform strategies.

1. Facility Reforms

Reforms that can be made to improve family engagement while youth are confined include:

-

- Keeping youth confined closer to their homes can give youth the opportunity to repair and renew family relationships while confined, and has been found to have a positive effect on recidivism.[169]

- Treating families with respect needs to be a “core operational principle” in the juvenile justice system.[170]

- Involving families “in a meaningful and respectful way in court proceedings and case planning processes,” as it can help to identify the youth’s needs and encourage more active support and assistance from the youth’s family.[171]

- Training juvenile facility staff on how to effectively engage families and work with those of different cultures in order to be most effective.[172]

- Eliminating barriers to and increasing capacity for family involvement by:[173]

- promoting family-friendly visiting hours and policies;

- discontinuing disciplinary policies that restrict a youth’s contact with families as punishment for infractions;

- helping families who have transportation needs;

- making family-centered practices such as access to support, information, and building relationships with staff a part of visits;

- using technology such as videoconferencing to connect youth who are housed far from their families;

- putting a process in place for families to provide input regarding their experiences; and

- establishing system/community advisory groups to identify and promote family involvement and engagement practices that improve communication between families and system stakeholders, such as the systems of care model.[174]

- Develop formal tools, structures, and protocols to ensure family and youth engagement. Methods include:[175]

- Training and tools used to help juvenile justice staff identify and engage the youth’s caregiver network.

- Using family genograms and eco-maps as visual tools to help staff engage youth and families in conversations to identify needed supports.

- Youth and family team meetings to bring them together with system personnel in a structured way for key system decisions and case planning.

- Family engagement specialists to help families understand and navigate the system and train system personnel on family engagement practices.

- Including family and youth voices on policy committees and surveys to get feedback on facility conditions and services.

2. Reentry Reforms

Families should be engaged “early and often” in order to smooth the reentry process by helping to identify the services and supports the youth will need.[176] Below are reform strategies to improve family engagement in the reentry process:

-

- Juvenile justice system personnel should ensure that there are “flexible and authentic opportunities for families to partner in the design, implementation, and monitoring of their child’s plan.”[177]

- As part of the process of engaging the youth’s family, juvenile justice systems should identify other supportive adults involved with the youth to include in the youth’s support team.[178]

- Families that need support should have access to effective resources and programs, such as evidence-based, research-based, and promising programs and models.[179] Examples include Multisystemic Therapy (MST) and Functional Family Therapy (FFT), both of which involve the entire family.[180]

- Work must be done to change the mindset and beliefs of many probation officers regarding working with families, and new models must often be adopted that value the inclusion of families and natural support systems.[181]

- Along with changing mindsets, training staff on how to effectively engage families and work with those of different cultures is also important. Additionally, staff should be able to work with youth in their home when needed.[182]

Strategies: Administrative

Alabama, New York, Washington, DC

- All of these jurisdictions are using the Youth Family Team Meeting (YFTM) model. This is a case planning system involving the youth, family members, mentors, teachers, case managers, service providers, and other supportive adults to develop treatment plans tailored to the strengths and needs of the youth.[183]

New York, Texas, and Washington, DC

- These states all provide orientations to the justice system for families of court-involved youth that are designed to help families understand and navigate the system.[184]

Lancaster County, Nebraska[185]

- Through receipt of Second Chance Act funding in 2011, Lancaster County developed and implemented a reentry project that included providing a family advocate to reach out to families of youth re-entering the community and provide support and guidance.

- Family advocates worked with 32 re-entering youth and their families (27% of all youth referred to the Reentry Project).[186]

- Family advocates often made referrals for community resources to help meet the family’s basic needs, such as housing placement, parenting classes, and budget assistance. They also worked to improve the communication between the family and system partners.

Ohio

The Ohio Department of Youth Services (ODYS) developed and implemented a number of tools to improve family engagement:

-

- Two models that encourage supervision staff to make frequent home visits include Effective Practices in Community Supervision and Functional Family Community Supervision.[187]

- The Family Finding program was adopted to make sure youth are connected to supportive adults. Staff are trained in how to identify and engage the youth’s caregiver.[188]

- The Juvenile Relational Inquiry Tool, developed by the Vera Institute of Justice, is used by ODYS to help the staff gather important information and family and social network “resources” to assist re-entering youth.

- Family Intervention Training was designed to strengthen how Juvenile Probation Officers (JPOs) work with families and assist them in identifying and improving problem areas.

- Video communication is used to connect youth in ODYS facilities with families, particularly for reentry planning.

- The Ohio Benefit Bank is a web-based system that allows JPOs to assist families in applying for public benefits such as food stamps and Medicaid/Medicare.

- The C.L.O.S.E. (Connecting Loved Ones Sooner than Expected) to Home Project is a free bus service for families to visit youth in ODYS facilities.

Pennsylvania[189]

- Peer advocates are used in the Pennsylvania juvenile justice systems and in other states to help family members of justice-involved youth navigate the system.

- Family advocates are used in Chester County, PA to support families: helping them to understand and navigate all the child-serving systems; providing referrals and accompanying family members to meetings as appropriate; and helping them to build supportive relationships with system providers and county staff.

- In Philadelphia, the Mental Health Association in Southeast Pennsylvania’s Parent Involved Network (PIN), provides several services to help families navigate the child-serving systems and to orient juvenile probation officers on working with families.

- The neighborhood-based Family Intervention Center was started in 1993 in Mercer County. It provides numerous activities for ongoing family involvement, including an overnight retreat for youth under family court supervision and their families.

- Family Group Decision Making (FGDM) is a project initiated by the Pennsylvania Supreme Court for the Dependency Court Improvement Project that is now also being used by juvenile courts. It is a restorative justice practice that involves youth, families, and other supportive individuals in ultimately developing a comprehensive case plan that addresses the concerns of both the family and the court.

- The PA Center for Juvenile Justice Training and Research is engaged in a statewide training effort to train interested juvenile probation officers in the Family Involvement in Juvenile Justice (FIJJ) curriculum, which offers practical instruction on family engagement and involvement in juvenile justice.[190]

Wisconsin[191]

- The State Division of Juvenile Corrections, Milwaukee Parenting Network, and the Social Development Commission partnered to develop “Creating Lasting Family Connections” (CLFC), a program of trained group facilitators to teach youth and families defenses against environmental risk factors such as substance abuse and violence. They learn interpersonal communication skills, refusal skills, and build stronger family bonds.

E. Addressing Youth Homelessness

A disproportionate number of homeless youth enter the juvenile justice system and other youth often become homeless upon or soon after their release from juvenile justice facilities.[192] Youth that become homeless after release experience higher risks for reoffending.[193]

1. Facility Reforms

Facility staff or probation officers can assist youth in finding family members or other significant positive adult role models who may be able to serve as support and/or potential caregivers for the youth.

Strategies: Administrative

Strategies: Administrative"]

Ohio

- Ohio has implemented programs that can help in identifying family members and other potential caregivers:

- The Family Finding program was adopted to make sure youth are connected to supportive adults. Staff are trained in how to identify and engage the youth’s caregiver.[194]

- The Juvenile Relational Inquiry Tool, developed by the Vera Institute of Justice, is used by ODYS to help the staff gather important information and family and social network “resources” to assist re-entering youth.

2. Reentry Reforms

In addition to continuing to help youth identify family and social network resources to assist them with reentry, assisting homeless youth with school enrollment is critical. Research has found that youth who were working or in school after release from a juvenile facility were less likely to recidivate.[195]

Strategies: Legislative

The McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act

- The McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act is a federal law that provides the right to immediate enrollment and full participation in school for homeless students.

- Youth who are or have been involved in the juvenile justice system are eligible for McKinney-Vento rights and services if they are homeless once they are released.[196]

- Youth have the right to enroll in the local attendance area school, or continue attending their school of origin, and attend classes while the school gathers the needed documentation.[197]

4. Reducing the Collateral Consequences of a Delinquency Adjudication

Youth returning from juvenile facilities face many challenges in reintegrating into the community. These hardships, or “collateral consequences,” include barriers to education, employment, military service, and public benefits. Reforms attempt to remove these barriers as well as protect the confidentiality of juvenile records and enable youth to seal (close to the public) or expunge (destroy) their juvenile records to best ensure that their past does not harm their future.

A. Confidentiality of Juvenile Records[198]

While a common perception is that juvenile delinquency records are private and protected, the confidentiality of these records has eroded significantly in recent years. A study released in November 2014 found that “A growing number of states no longer limit access to records or prohibit the use of juvenile adjudications in subsequent proceedings.”[199]

-

- Juvenile records refer to all the documents created from the time of a youth’s arrest, including police reports and charging documents, witness and victim statements, court-ordered evaluations, fingerprints, and DNA samples.

- Many of these records contain sensitive information, including details about a child’s family, social history, mental health history, substance abuse history, education, and involvement with the law.

- When this information is not confidential, “it can stigmatize the youth and erect barriers to community reintegration.”[200] For example, juvenile records that are public and accessible to employers and landlords are often used to deny youth jobs and housing.

In a report released in November 2014, the Juvenile Law Center developed core principles for protecting the confidentiality of and access to juvenile records during and after juvenile court proceedings. Below are some of their key recommended state statute reforms:[201]

-

- Specifically, state that confidentiality protections apply to all information in law enforcement and court records, and detail the type of information contained in these records.

- Make clear that juvenile records shall be filed and kept separately from adult records.

- Prohibit public inspection of juvenile court and law enforcement records.

- Limit access to juvenile record information to individuals connected to the case, which may include juvenile court personnel, the youth and his or her attorney, the youth’s parents, supervising agencies, and the prosecutor. Limited access may be granted to individuals conducting research.

- Put protections in place for juvenile record information released to government agencies and schools.

- Confidentiality exceptions are only permitted by court order.

- Provide sanctions for the unauthorized sharing of confidential juvenile record information (except for youth who share their own information).

Strategies: Legislative

The Juvenile Law Center recently released a national scorecard on juvenile confidentiality. States that restricted the availability of court records to law enforcement or court personnel and did not make exceptions to their general rules of confidentiality received the highest score. The states receiving the top ranking of five stars for their laws on the confidentiality of juvenile records were (in order): Rhode Island, New York, Vermont, Wyoming, Nebraska, and Ohio.[202] Detailed information on the laws in each of these states can be found here.

B. Sealing and Expunging Juvenile Records

Both sealing and expunging juvenile records are recommended methods to further protect the confidentiality of juvenile records and help to reduce the barriers to youth re-entering their communities.

- “Sealing” a juvenile record generally means that the records are closed to the general public but remain accessible to certain agencies and individuals, although criteria for access differs by jurisdiction.[203]

- “Expungement” generally refers to erasing a juvenile record as if it never existed so that it is no longer accessible to anyone. In some cases, though not in all, both physical and electronic records are destroyed.

- However, these definitions are not ironclad. In some states, such as Delaware, “expunged” records are treated more like sealed records in that they are still available to certain parties.[204]